Author's posts

Apr 21

Friday Live Chat

It’s back, the Friday Live Chat. You know what to do – just use the comments section below. We’re in…

Apr 20

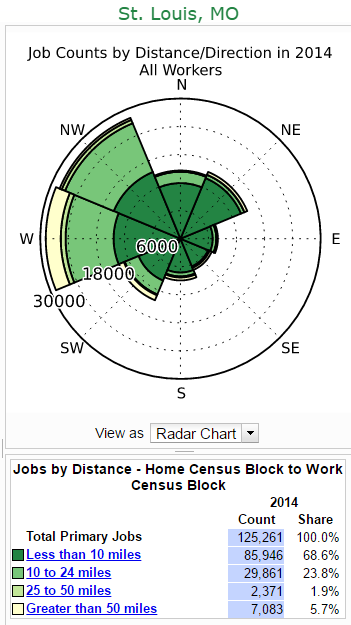

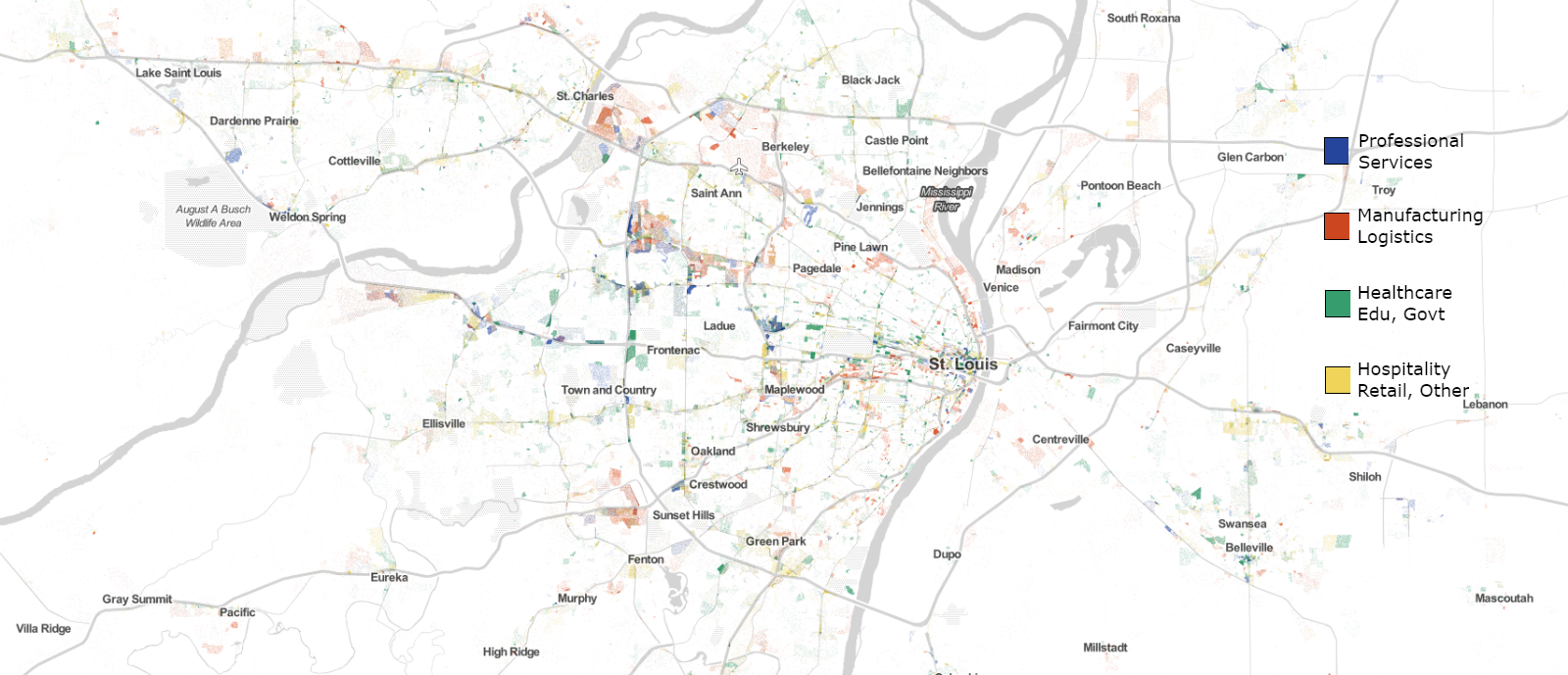

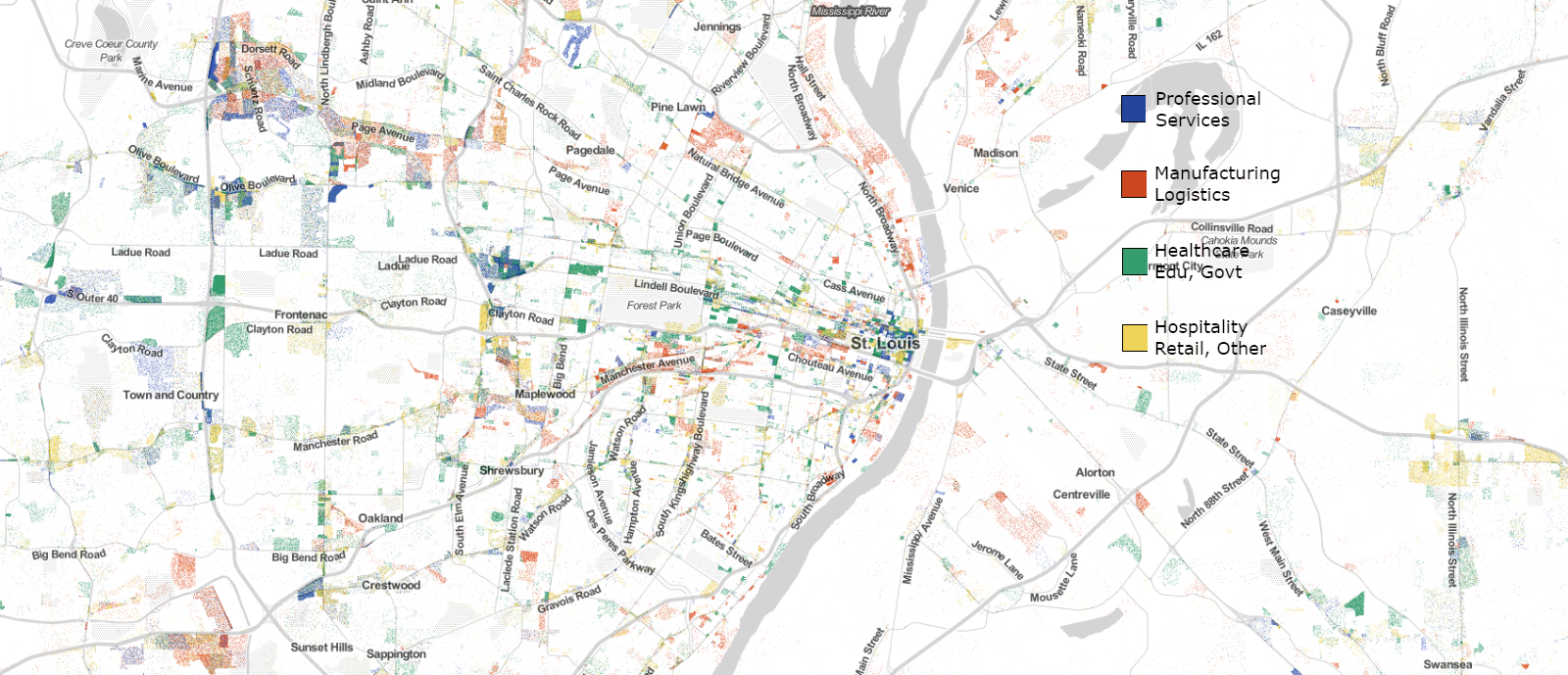

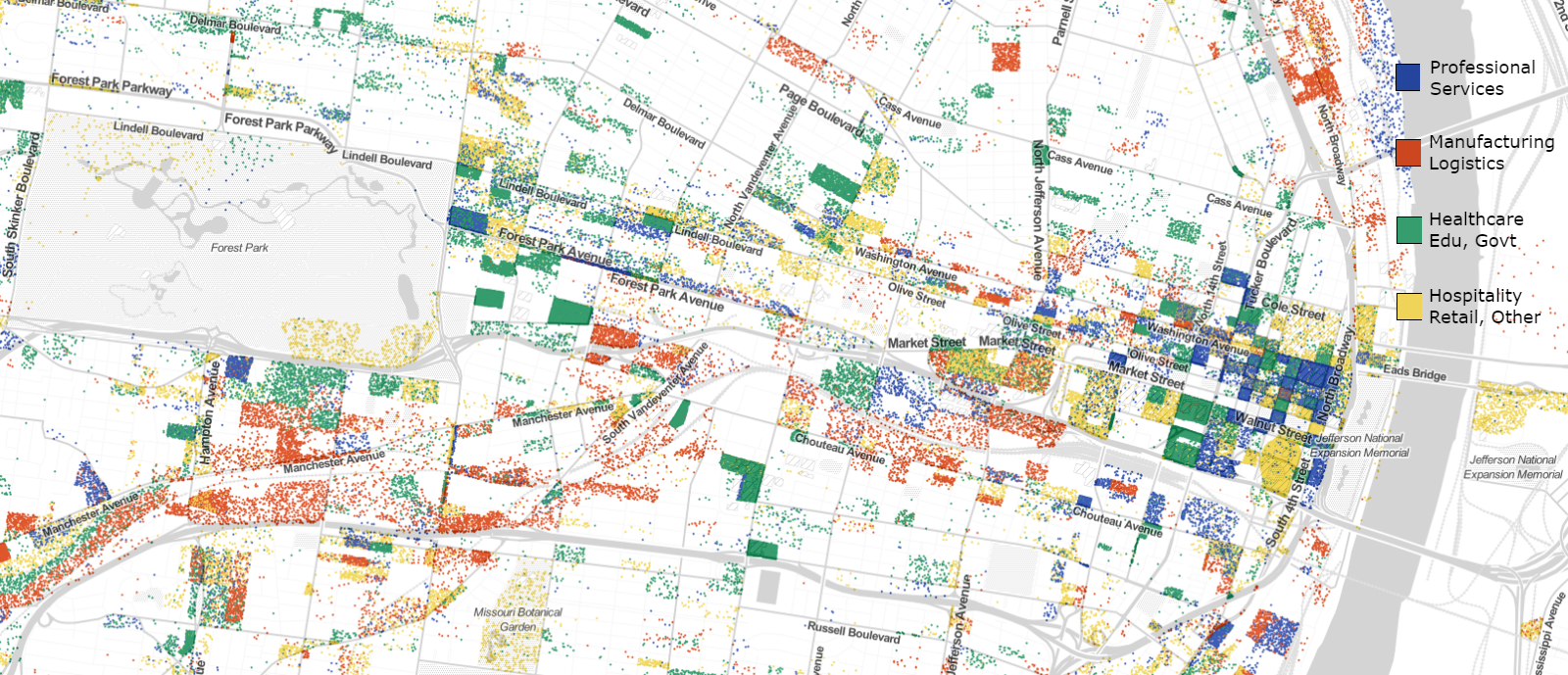

Understanding St. Louis: Asymmetry of Job Counts by Distance/Direction

Downtown St. Louis is the center of the region. Sort of. Downtowns, despite their long-waning position as anchor employment and shopping districts, continue to serve as a sort of ceremonial “center” in most metro regions.

Downtown St. Louis is the center of the region. Sort of. Downtowns, despite their long-waning position as anchor employment and shopping districts, continue to serve as a sort of ceremonial “center” in most metro regions.

Downtown is generally where City Hall can be found, as well as the tallest buildings, often the sports arenas, the courts, some convergence of transit, etc. Downtown is where a region celebrates. It’s where you find championship parades, conventions, the largest civic events, the marathons, festivals, that Arch, and more.

But downtown St. Louis is far from the actual center of the region. Our population center lies somewhere between Olive Boulevard and I-64 along I-270. While the combined population of St. Louis City, St. Louis County, and St. Charles County has grown just 1.6% since 1970, the population center of the region has fled west.

At the same time, the Metro East has continued to lose jobs and residents. From 2000-2010, the Illinois counties of the Metro East lost a greater percentage of their population than did the City of St. Louis (8%).

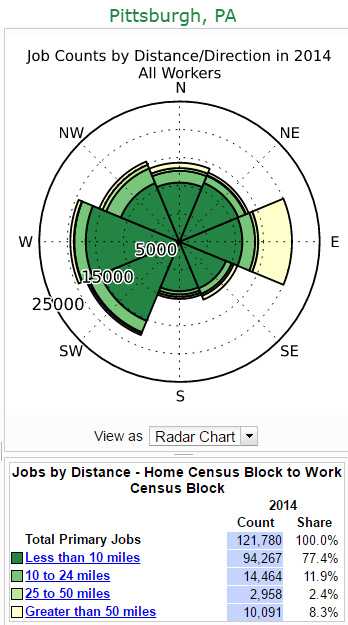

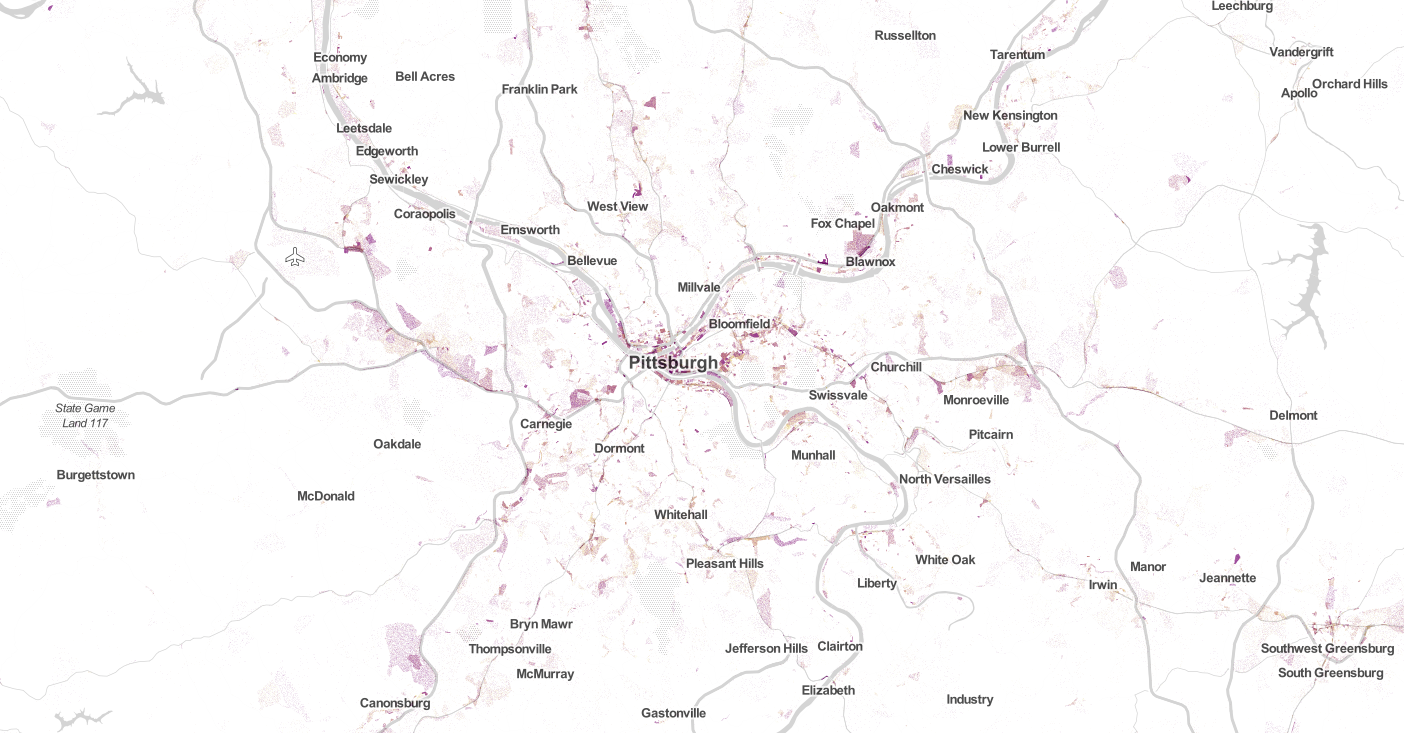

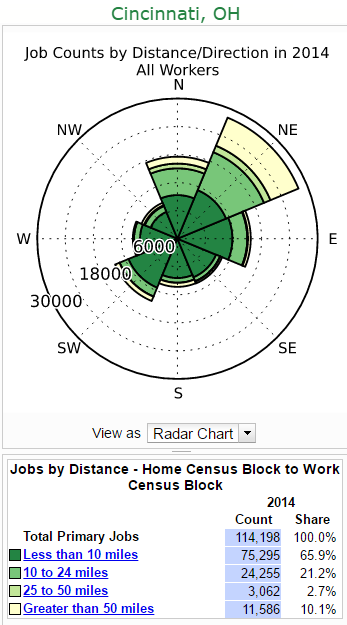

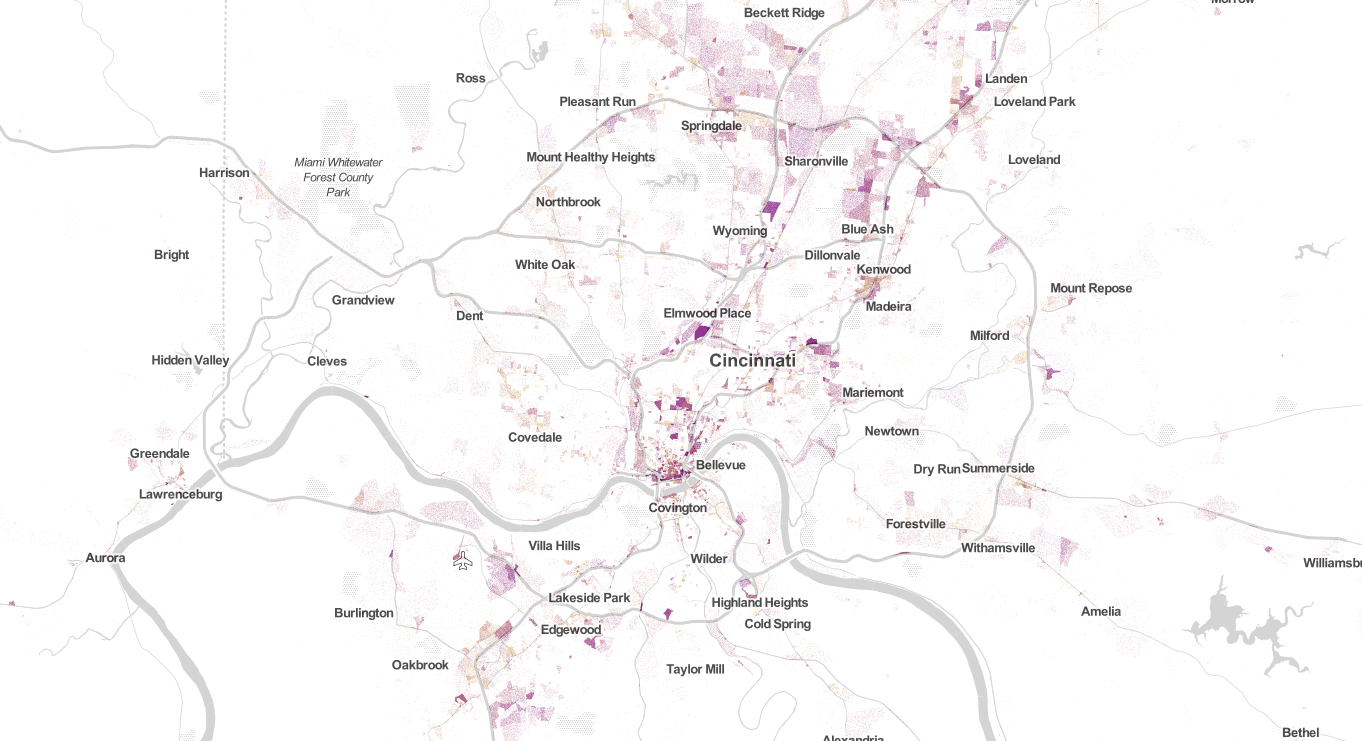

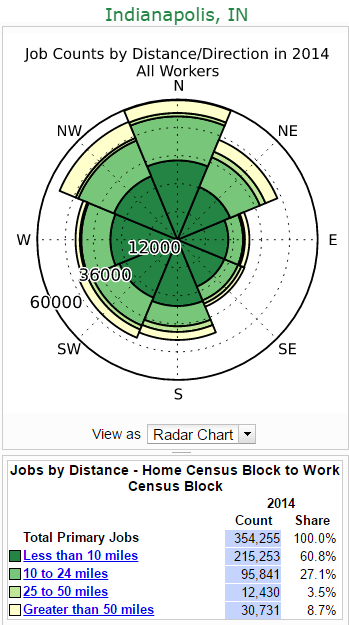

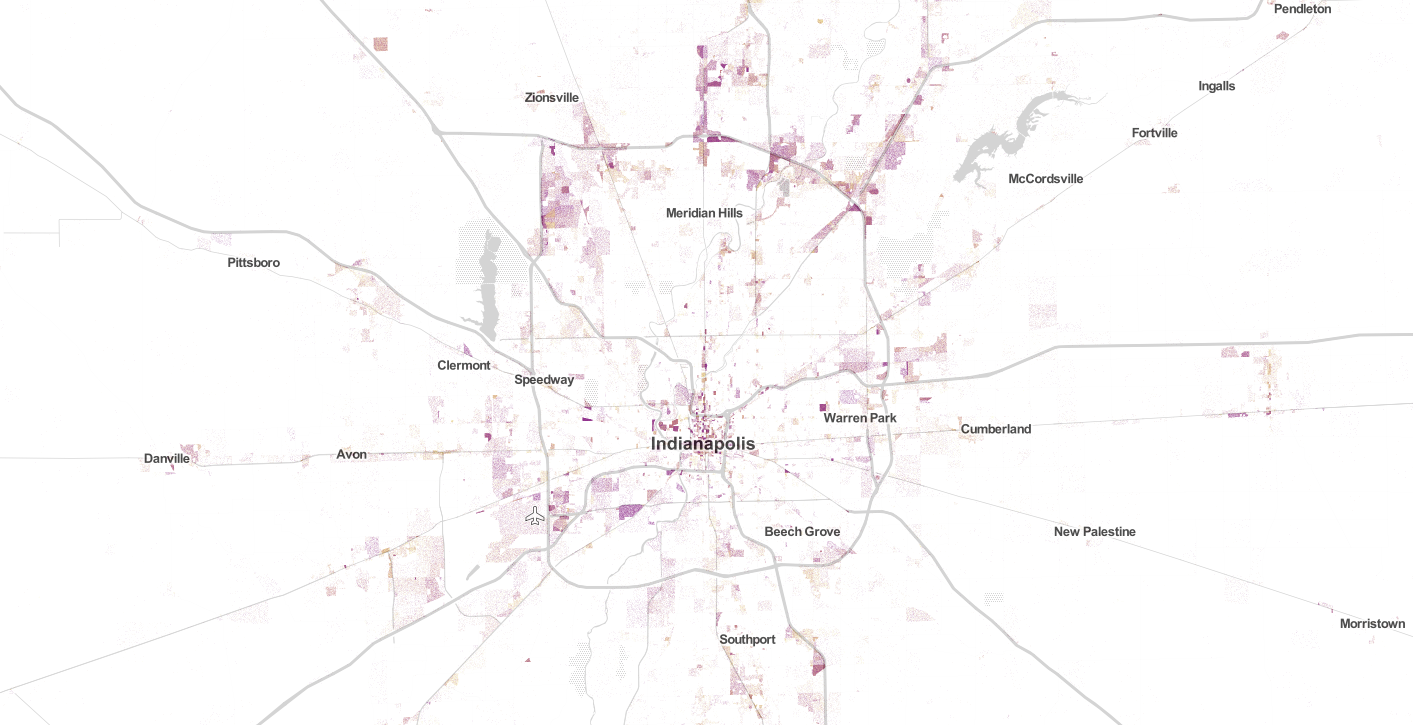

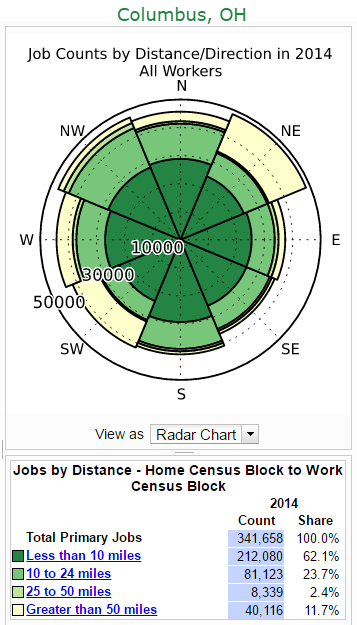

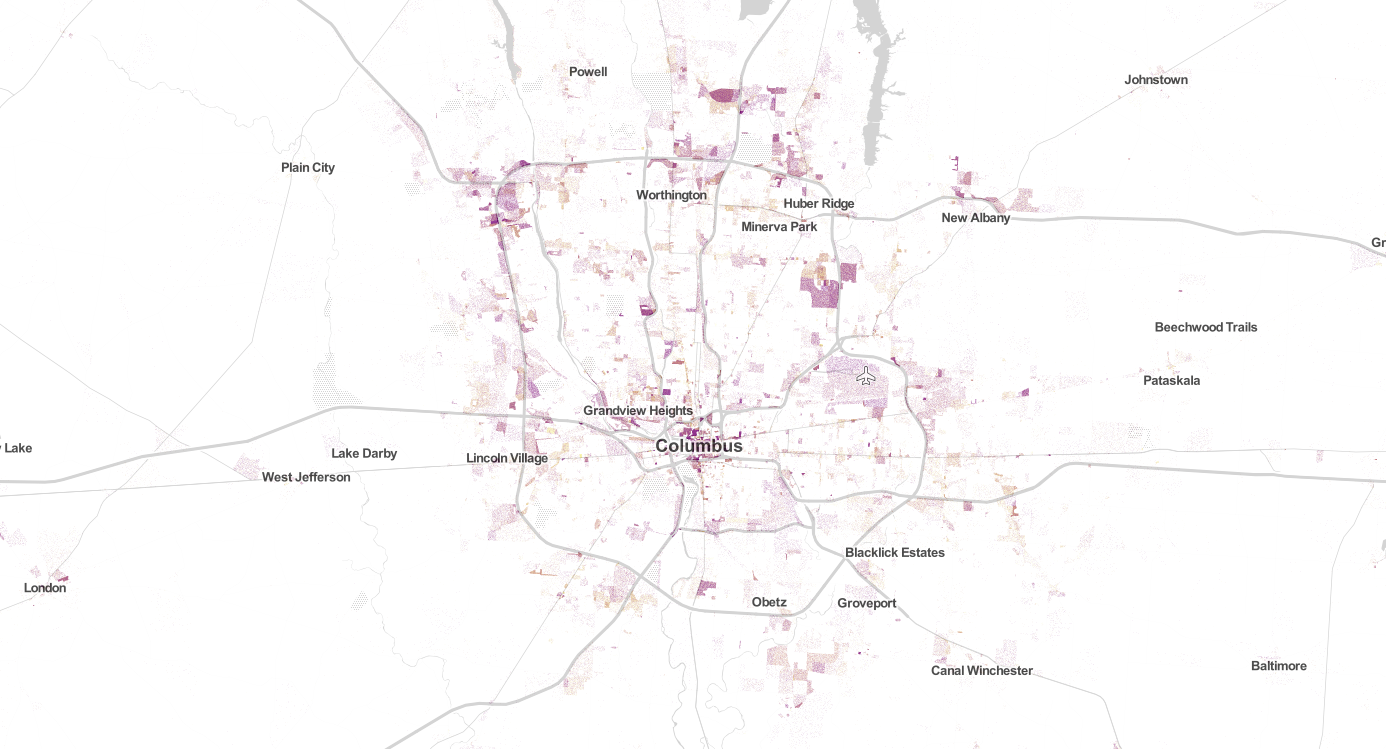

And while downtowns across the Midwest have lost employment and retail density, St. Louis may be unique in how displaced our downtown has become from jobs, retail, and residents. Looking at the cities of Columbus, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and St. Louis highlights the difference.

Both Columbus and Indianapolis show significantly greater job sprawl than St. Louis, but their downtowns have remained very nearly the center of their respective regions. Pittsburgh is significantly more compact and centered. Cincinnati is heavily skewed but shows greater balance, and its asymmetry is created in part because of development along the I-75 corridor to nearby Dayton.

So what? Well, we can imagine downtown St. Louis as the center of the region but must recognize that it is not. How we understand this should inform policy and planning decisions regarding transit, retail, development subsidies and more. That is, you simply can’t create development strategy without recognizing the unique position of downtown St. Louis.

By income:

Employment dot maps: http://www.robertmanduca.com/projects/jobs.html

Jobs distance and direction radar maps: https://lehd.ces.census.gov/

Apr 18

An Assessment of the Effectiveness and Fiscal Impacts of the Use of Development Incentives in the St. Louis Region

Executive Summary

In the last 20 years local governments in the metropolitan St. Louis region have diverted more than $5.8 billion in public tax dollars to subsidize private development through the use of various financial incentives, including tax increment financing, special taxing districts and tax abatements. Municipalities, counties and states used these development incentives in the competition to lure tax-generating businesses to their specific jurisdiction. These incentives subsidized new developments by taking a portion of what otherwise would have been paid as taxes and instead diverting them to the private developer to finance the development.

In response to concerns about the long-term effects on the economic health of the region and the fiscal well being of local governments, the East-West Gateway Board of Directors (made up of the region’s local elected officials) took the following action:

…authorize the staff to undertake a study of the effectiveness of local development incentives to help determine potential actions by the Board. The study should include an inventory of the amount of previous incentives granted by local government and the resulting economic activity from the projects financed through incentives. The study should also determine the effect of local development incentives on the ability of local governments to finance essential public services and the degree to which the extensive use of incentives contributes to economic and racial disparities in the region.

This research documents that the use of these tax incentives has been ineffective both as a way to increase regional sales tax revenue or to produce a significant increase in quality jobs. It also clearly has not helped municipalities avoid fiscal stress or had a general beneficial economic impact on the region.

Over the same period, the region has made modest employment gains, primarily in the service sector. Job growth overall has been sluggish, growing at a rate of about 0.8% annually from 1990 to 2007, with a significant slowdown after the year 2000, when the growth rate fell to 0.2%. Retail employment is of particular interest because, according to East-West Gateway estimates, about 80% of tax increment financing (TIF) and transit development district (TDD) incentives have been for retail oriented development. From 1990 to 2007, retail sector employment grew from about 142,100 jobs to 147,500, a gain of about 5,400 jobs. Since 2007, during the recession, both sales tax revenues and job growth have decreased significantly, as might have been expected.

In addition to the $2.5 billion documented in East-West Gateway’s Interim Report, this Final Report provides estimates of the additional tax revenue forgone through tax abatement programs in both states as well as tax revenue allocated to private development in the region through the use of state tax incentive programs. This report refines some of the data used in the Interim Report for TIF and special taxing districts, and includes more recent data, through 2009.

There are examples of the effective use of development incentives but they are greatly outnumbered by the projects that produce localized benefits at a high cost with little or no demonstrable economic benefit. The problem is not the use of incentives, but how they are used. The purpose of this report is to challenge community leaders, both in the public and private sectors, to reconsider the role of local development incentives as part of a comprehensive regional economic development strategy and to provide the necessary information to develop policy and legislative changes that might produce real and sustainable economic growth for the St. Louis region.

This Final Report includes research by East-West Gateway staff and research commissioned from area universities, and contains the following elements:

- An inventory of the use of development incentives in the St. Louis region

- An account of the local and regional effects of those tax incentives

- An assessment of the local government finances

- Conclusions and legislative recommendations

Based on the findings of this research, we have reached the following conclusions:

1. There has been a massive public subsidy of private development – more than $5.8 billion – in the last 20 years across the St. Louis region. The $5.8 billion diversion of public tax dollars to private developers is a conservative conclusion based upon the best available data. About half of this has been allocated through two types of programs that are predominantly used for retail development: tax increment financing (more than $2 billion) and special taxing districts (more than $500 million).

2. Evidence exists that the use of TIF and other tax incentives, while positive for the incentive using municipality, has negative impacts on neighboring municipalities. An examination of sales tax revenues and the use of TIF demonstrate that declining shares of sales tax revenue in one municipality often coincides with the use of incentives and growth of tax revenue share in neighboring municipalities. Zip codes that have TIF-related investment have been found to have an increase of jobs in the active TIF years, but that TIF use was associated with a decrease in jobs elsewhere.

3. Local governments in the region are under fiscal stress. A significant number of municipalities have experienced declining sales and/or property tax revenues, particularly when these revenues are adjusted for inflation. A significant number of municipalities faced budget deficits, layoffs and service cuts between 2000 and 2007, even though that was a period of time when the economy had generally fared well. In a survey of municipal officials, many indicated they had serious concerns about the long-term fiscal sustainability of their cities.

4. The use of tax incentives has exacerbated economic and racial disparity in the St. Louis region. Historically, tax incentives to private developers are less often used in economically disadvantaged areas and their more frequent use in higher-income communities gives those jurisdictions what amounts to an unneeded, extra advantage. Tax incentive tools such as v Chapter 99 and Chapter 353 tax abatements and TIFs were used repeatedly in the central business district and the west end of the city of St. Louis while they were used sparingly in depressed sections of North St. Louis. Throughout the region, areas of concentrated poverty begin at a distinct disadvantage when trying to compete for customers, businesses and jobs and are further handicapped when higher-income communities receive additional advantages through diversion of tax dollars to private developers via tax incentives.

5. A complete database of Missouri municipal finances is needed. The Illinois Comptroller has an electronic database of all taxing districts. In Missouri, such a system should be developed to help local officials to make informed decisions, and to provide transparency and accountability. The current system in Missouri involves municipalities filing hard-copy reports with the State Auditor Office.

6. Across all incentive programs, the provisions for uniform reporting of revenues, expenditures, and outcomes (jobs, personal income, increases in assessed value, etc.) are remarkably weak, particularly considering the involvement of public funds. In 2009 the Missouri legislature modified TIF and TDD statutes to require better reporting and, in the case of TDDs, a financial penalty for failure to submit annual financial reports. While these are improvements, it is still true that the state agencies that have the responsibility for maintaining reports have inadequate resources to discharge those responsibilities. Further, there is no mechanism to require a private project sponsor to deliver economic outcomes, or to allow the taxpayers to recoup the value of local tax incentives if those outcomes don’t happen (sometimes known as “clawback” requirements). Those accountability provisions apply to certain state subsidies like the Missouri Quality Jobs Act, but are absent for local incentives.

7. Educate the voting public on taxes and how public services are funded. Many citizens lack an understanding of how government is funded and the tradeoffs required to balance budgets. This fact, combined with a growing mistrust of government has led citizens to disengage from the process. Local governments have increasingly turned to using economic development incentives, particularly TIF and special taxing districts, as a mechanism to fund services. They are tools that local governments can use to control an additional revenue stream without a popular vote and avoiding legislative caps on major revenue sources. This is not a sustainable means of financing government. We must instead, educate the public on the true costs of services, the tradeoffs that exist and the options for funding public services.

8. There should be a complete database of public expenditures and outcomes for all publicly supported development projects. Because of the lack of widely available information, elected officials and the public cannot possibly make reasoned decisions about the expenditure of tax dollars to produce economic growth. Without that information, it is not possible to know whether local governments are getting value for those expenditures, and because there is no accountability for outcomes, the public cannot recover those expenditures in the event that outcomes are not achieved. One exception is the city of St. Louis, which has required a “clawback” provision in its redevelopment agreements since 2005.

9. Focusing development incentives on expanding retail sales is a losing economic development strategy for the region. The future of sales taxes as a principal source of revenue for local governments should come into question for several reasons: its inherent volatility; the likelihood of a long-term restructuring of retail trade; increasing level of sales taxes discourages spending and local sales in favor of non-taxed internet sales; and, the motivation this tax source provides to focus scarce tax dollars on incentivizing a type of development that appears to yield very limited regional economic benefit. As local governments come under increasing fiscal stress, the impacts of billions of dollars in forgone revenue will become increasingly apparent.

10. Broad measures of regional economic outcomes strongly suggest that massive tax expenditures to promote development have not resulted in real growth. While there are certainly short-term localized benefits in the use of incentives, regional effects are more elusive. Development incentives have primarily acted to redistribute spending and taxes. While distribution effects might yield broader economic benefits when used to redevelop economically distressed communities, when incentives are used in healthy and prosperous communities the regional effect may be to destabilize the fiscal health of neighboring areas. This conclusion particularly applies to retail development. While there is ample justification for tax expenditures on retail development in underserved areas, overall there seems little economic basis to support public expenditures for private retail development. Despite massive public investment, the number of retail jobs has increased only slightly and, in real dollars, retail sales or per capita spending have not increased in years. Furthermore, the region has seen a shift from goods producing (higher paying jobs) to service producing (typically lower paying) jobs, suggesting that although there are more jobs, they are of lower quality. Household income is lower and increasing more slowly than in most of our peer regions.

11. Set aside old ways of thinking and adopt an agenda for regional fiscal reform. In 2008, the Metropolitan Forum brought together a national panel of experts who studied the St. Louis region, concluding the region needs to adopt new ways of thinking. This research supports the need for a regional solution to the problematic overuse of development incentives and the fiscal crisis in which local governments find themselves. Local governments need support to change and adopt a better strategy for the future. Regional fiscal reform will only be possible through a large-scale collaborative process that cuts across jurisdictional boundaries and is inclusive of all sectors and levels of government.

Read report: An Assessment of the Effectiveness and Fiscal Impacts of the Use of Development Incentives in the St. Louis Region

An Assessment of the Effectiveness and Fiscal Impacts of the Use of Development Incentives in the St. Louis… by nextSTL.com on Scribd

Apr 18

Morgan Ford in TGS May See Three-Story, 26-Unit Mixed-Used Project

Planning and design work is progressing for a mixed-used project on Morgan Ford Road in the city’s Tower Grove South neighborhood. An envisioned project would replace a car wash as Morgan Ford and Connecticut with a three-story, 26-unit apartment building with 6,000sf of street-level retail.

The 0.42-acre site is now owned by George Smith Partners out of Los Angeles. Among the firm’s team is Vice President Kyle Howerton, a St. Louis native and graduate of Saint Louis University. Initial site design is by JEMA.

From JEMA:

JEMA’s design for a mixed-use residential and retail ground-up building located in south St. Louis is moving forward. The project is located on Morganford Road and is aptly named MOFO. The design concept utilizes a series of solid and perforated corten steel panels, iron spot brick, and wood panels creating a proportion and rhythm reminiscent of historical south St. Louis buildings and streetscapes.

{Morganford Road elevation}

{Morganford Road elevation} {Connecticut Road elevation}

{Connecticut Road elevation} {Morganford and Connecticut}

{Morganford and Connecticut}

Existing site:

About Alex Ihnen

Apr 18

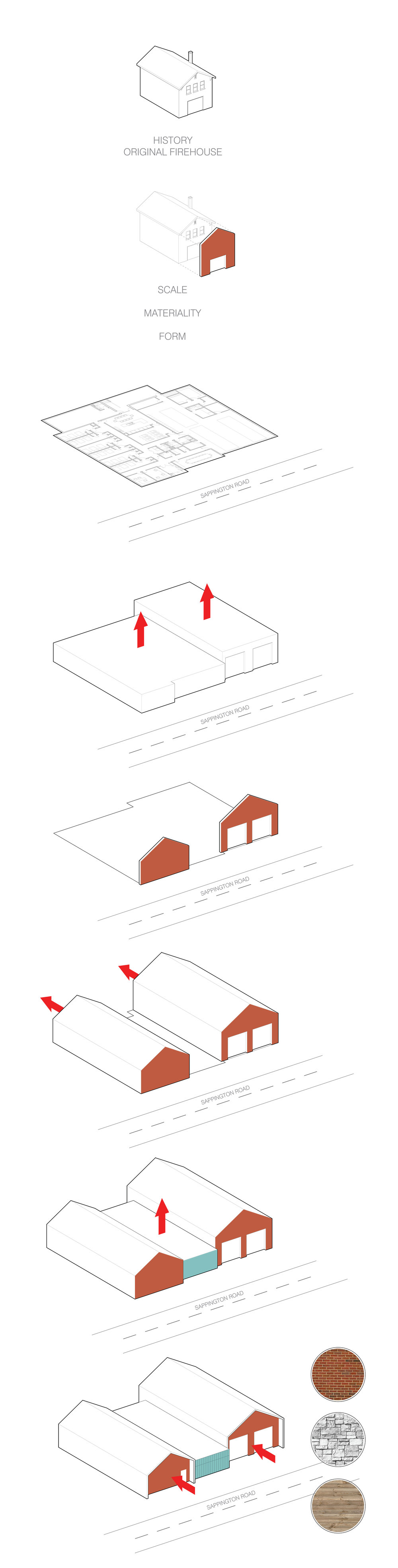

Glendale’s New City Hall, Police HQ, and Fire Station by JEMA Moves Ahead

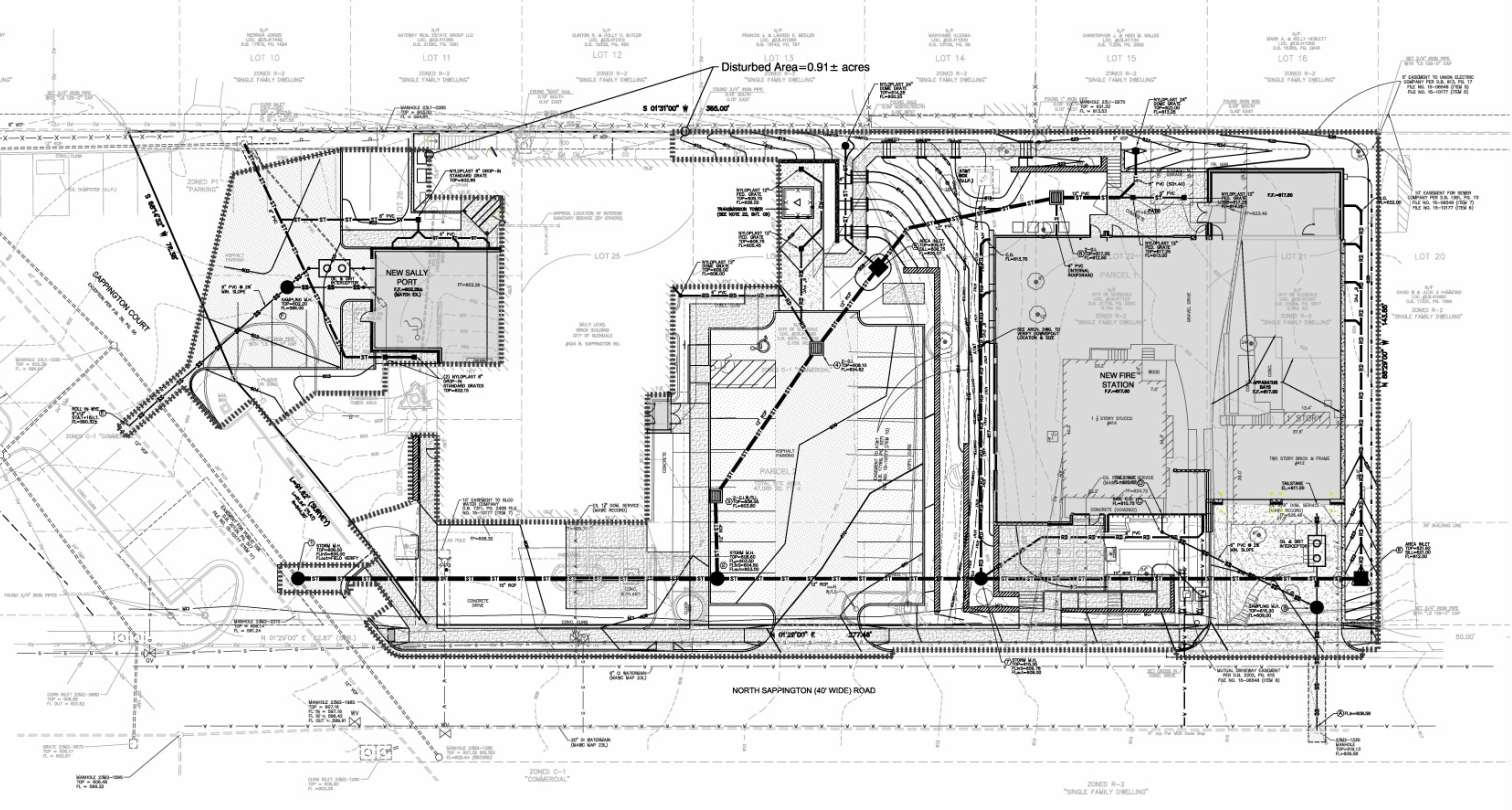

This past year, residents of the suburb of Glendale, MO approved an $8M bond issue to construct a new Glendale Municipal Center. The project’s $5.2M construction cost is being financed two new taxes, a property tax at 34.6 cents per $100 assessed value, and a new sales tax of .25%, which began this year.

JEMA was awarded the design contract this past fall. The project has now been released for construction bids. Once a builder has been selected, construction should take approximately 18 months. Glendale’s existing municipal building dating from 1915 will be renovated as a new City Hall and Police headquarters. Two homes were demolished to the south to make way for a new fire station.

Glendale, MO is a community of 5,925 residents per the 2010 Census. The town’s population peaked in 1960 at 7,048, declining by 13.6% in the 1970s. Since 1980, the population has declined less than 2%. The mayor of Glendale is Richard J. Magee, who was elected to a sixth term in 2015.

Existing conditions:

The two homes demolished to make way for the new fire station:

Project models and design concept from JEMA:

About Alex Ihnen

Apr 15

Changes Present Better Urban Design for Lafayette Square Praxair Site

When the Pulte Homes and Killeen Studio Architects plan for infill at the long-vacant Praxair site in Lafayette Square hit a road bump a couple weeks ago, we were surprised. Reaction to the very conventional proposal on this site and various social media was almost entirely positive. If you can please this crowd…well, we just thought it would likely sail through.

It turns out that we had switched off our NIMBY radar for maintenance and missed the looming opposition. Residents of Lafayette Square turned out to the city’s Preservation Board meeting, where the Cultural Resources Office was to recommend initial approval, and suddenly the project was stalled. Seems that being against something is still a greater motivator than being for something.

Anyway, Pulte and Killeen apparently listened and returned to the drawing board. The project is scheduled to go back before the Preservation Board later this month. Both the site plan and building design have seen changes.

The new site plan shows Lasalle Street no longer connecting through the development to MacKay Place. A new north-south street enters the development from Chouteau. This allows for an incredibly important change in the orientation of the rowhouses.

In the first site plan iteration, the interior streets were really 26-foot wide alleys, fronting large garage doors and the rear of many townhomes. The front of those residences faced one-another across grass courtyards. The revised plan smartly shows all east-west facing garages fronting 15-foot alleys, with the new 26-foot wide street allowing for every unit to face a street. This arrangement results in the loss of two units, but conforms to neighborhood code, and presents a much more urban form.

There are still shortcomings with the plan, but residents opposed to the development surely see these as features and not bugs. Lasalle should connect through to MacKay. And the alley behind the homes fronting Chouteau should connect to both Missouri and MacKay.

Still, it’s an improvement, and the revised site plan means that this will not be the dominant view within the development:

The second significant improvement is the introduction of several new Historic Model Examples (HMEs). With 62 units, presenting some variation in facades and materials is important in creating an interesting and attractive streetscape.

Revised site plan (April 2017):

March 2017 site plan:

Historic Model Examples (HMEs):

________________________________________

From our previous report: Design and Site Plan for 64 Townhomes at Lafayette Square Praxair Site Presented

Lafayette Square appears close to finally developing the long-vacant Praxair site. Pulte Homes plans to build 64 Killeen Studio Architects-designed townhomes on the Praxair site bounded by Chouteau, Missouri Avenue, MacKay Place and a separate parcel fronting Hickory Street to the south.

The site is within the Lafayette Square local historic district, which stipulates requirements for a new construction project such as is being proposed. The city’s Cultural Resources Office is recommending the Preservation Board grant preliminary approval to the project with several provisions: that rear elevations of buildings within two parcels of public streets be brick; sidewalks be placed on both the north and south sides of the re-opened LaSalle Street; and of course that final plans and materials be reviewed by CRO.

On June 25, 2005 the Praxair site along Chouteau Avenue in the city’s Lafayette Square neighborhood caught fire. The site served as storage for gas tanks, which began to explode, sending debris onto the rooftops of surrounding homes and businesses. In all, as many as 8,000 gas cylinders exploded, and the fire took a full five hours to get under control. Interstate 64, just more than 1/3mi to the north, was closed. The Cardinals game was delayed.

The 4-acre site has sat vacant since. The adjacent Lafayette Walk townhome development stalled after 31 of 37 planned units were completed in 2008. That project was announced in 2004 and suffered from bad timing as units began to sell in late 2007. In recent years, development has picked up in the neighborhood with Mississippi Place on the east side of the park, infill along Park Avenue, and new single-family homes centered on Dolman Street.

Lafayette Walk townhomes adjacent to Praxair site.

Existing Praxair site:

Continue reading: Design and Site Plan for 64 Townhomes at Lafayette Square Praxair Site Presented

Apr 14

Friday Live Chat

It’s back, the Friday Live Chat. You know what to do – just use the comments section below. We’re open…

Apr 14

Weese & Kiley’s Mid-Century Forest Park Campus Threatened

Thousands of students descended on the modern new campus on opening day in September 1967. There were housewives and veterans, recent high school grads and draft dodgers. They were future nurses and medical assistants, technicians, musicians and tradesmen. Many were educationally disadvantaged students who otherwise had little chance of an education beyond high school.

Many had come to this location as children, for they gathered at the site where once had stood The Comet, Amerca’s tallest and longest roller coaster with nine drops, a double dip and a 500-foot tunnel. On Friday July 19, 1963, after a restaurant fire, the Comet had watched as the rest of Forest Park Highlands burned to the ground beneath it. The Comet was disassembled and the charred remains of the Highlands bulldozed. In its place rose what then was known as Forest Park Community College.

Many had come to this location as children, for they gathered at the site where once had stood The Comet, Amerca’s tallest and longest roller coaster with nine drops, a double dip and a 500-foot tunnel. On Friday July 19, 1963, after a restaurant fire, the Comet had watched as the rest of Forest Park Highlands burned to the ground beneath it. The Comet was disassembled and the charred remains of the Highlands bulldozed. In its place rose what then was known as Forest Park Community College.

Opening in 1967, college construction would continue for three more years. By 1970, William Moore could note in Against the Odds that 307 other community colleges already had sent representatives to Forest Park Community College to observe and learn. Forest Park was designed to be a leader that other colleges follow.

And the best designers lay behind plans for the new campus. From 1964 to 1967, acclaimed mid-century architect Harry Weese and his son Ben had worked with landscape architect Dan Kiley—the father of modern landscape architecture—to design an integrated, modern campus.

Fifty years later, St. Louis Community College plans to demolish two of Weese’s mid-century towers at the heart of the complex on Oakland Avenue and construct a new Allied Health building on Kiley’s lawn.

Harry Weese, Urbanist & Preservationist

A midwesterner trained at MIT and Yale, Harry Weese studied urban design at Cranbrook under Eliel Saarinen. His fellow students included Charles and Ray Eames, Harry Bertoia and Florence Knoll. He worked briefly for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in New York during the late 1940s before opening his own practice in Chicago.

Harry Weese loved old buildings, loved cities, loved public spaces, loved modern design and loved alcohol. All these he loved greatly. Before the last of these loves finally took its toll, Weese made major contributions in all of the other areas. As a juror in the competition to design the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, his was the voice that advocated against great opposition for Maya Lin’s wall of names. In his 1998 obituary, the New York Times describes Weese as “the architect […who…] produced some of the most powerful public spaces of our time.”

Weese was among the second generation of modernist architects like Eero Saarinen, I.M. Pei and Philip Johnson. Though Weese never achieved the same international fame of Saarinen or Johnson, in some way his impact was greater. A rare advocate of historic preservation among modernists, Weese was partly responsible for saving Chicago’s Navy Pier, and in 1978 he even proposed that that city’s “L” stations be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1967, he undertook the renovation of Adler and Sullivan’s Auditorium Theater in Chicago. He supervised the restoration of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and Union Station in Washington.

Weese was also unabashedly an urbanist. Weese argued that the post-war boom in suburban development was wasteful and inherently unsustainable, and he advocated for higher density middle-class housing with access to public spaces and amenities. In an article in Places Journal, Ian Baldwin argues that Weese’s “unrelenting urban boosterism and deep commitment to public life and preservation made him arguably more influential than any of his contemporaries.”1

Weese’s Kinder, Gentler (Humanistic) Brutalism

Weese brought an independent voice to his design work. At a time when modern architecture conjured images of cold and expansive concrete brutalism, Weese brought in warmer materials and local textures. His 1958 United States Embassy in Accra, Ghana included louvered mahogany bays floating above delicate white pilotis. The overall effect is organic, warm and modern.

In his 1962 First Baptist Church in Columbus, Indiana—the church is a national historic landmark—Weese made use of warm red brick in a sculptural design that makes for a kinder and gentler interpretation of the brutalism then dominant in Europe and America. When much modern architecture had become formulaic, Weese’s 1968 Seventeenth Church of Christ, Scientist on Chicago’s Wacker Drive provided an expressive solution to an awkward site along the Chicago River, and it did so with a massing that addressed the monumental scale of the neighborhood.

1962 First Baptist Church—Columbus, Indiana:

1968 Seventeenth Church of Christ, Scientist—Chicago:

Much of Weese’s work is in the warmer materials of stone, brick, and wood. Yet he also experimented with steel, albeit the warm corten steel beloved of so many modern sculptors. In The Architecture of Harry Weese, historian Robert Bruegmann notes designs that push far beyond the orthodox International Style of Mies van der Rohe. Weese’s 1968 Shadowcliff is a home office suspended from corten beams cantilevered out from a Wisconsin rock face high above Lake Michigan. A window in the floor allows for views in all directions.

The Graham Foundation describes the work of Weese and Associates as syncretistic.

Although Weese was a self-avowed modernist, his early work … disregards numerous modernist conventions. Unfettered by the philosophical preconceptions of Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius, Weese appears, like Saarinen and Aalto, to subscribe to a more humanistic modernism. … Weese’s buildings provide insight into a uniquely American approach to mid-century modern architecture that never lost sight of the social, political, and economic realities of contemporary life.2

Weese is perhaps best known for his design for the Washington Metro. At the height of the Cold War, the Metro’s graceful concrete vaults—now threatened with white paint by government bureaucrats—were designed to contrast with the fussy ornament of Moscow’s Stalinist subway stations. Good modern design has an economy of form, and Weese’s Metro remains a monument to the subtlety of the modern vision.

The Design for the College at Forest Park

The Junior College District of St. Louis and St. Louis County planned for a college on the site of the Highlands. It was one of three colleges backed by a $47 million bond issue, which at the time made it the most ambitious building program in the history of public higher education in the United States. According to the District minutes, the 35-acre Forest Park site was intended to house 7,000 full-time day students.

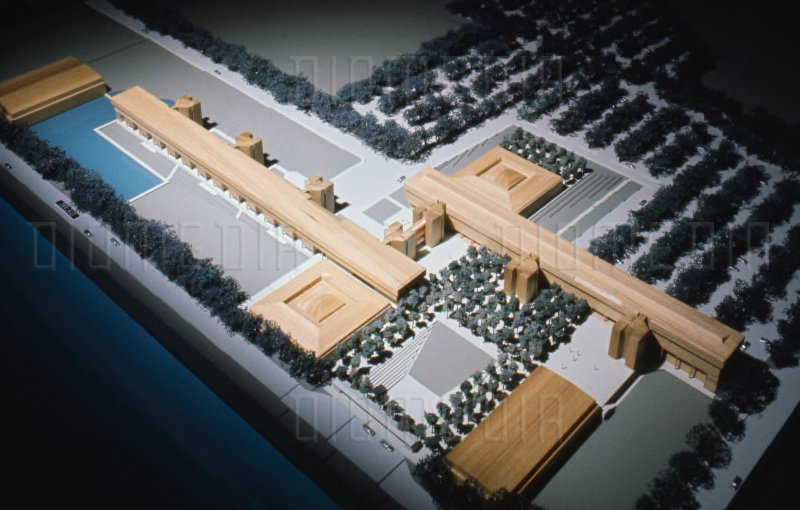

For their design for Forest Park Community College, Harry Weese and Associates and Dan Kiley envisioned a four-story complex arranged along two horizontal spines. Terraces and a sunken gathering space would tie the buildings together. Circulation would be by exterior walkways along the spine on the ground floor. These walkways would connect individual towers. Lecture halls were to be on the lower level, with labs on the top floor and classrooms and offices on the floors in between.

Kiley recently had finished his role with Eero Saarinen in designing the grounds of the Gateway Arch. For the college, he and Weese planned a series of courtyards connecting the spines at the western end of the campus. Trees would shadow the courtyards, the largest of which would step down to a large fountain, providing an exterior auditorium when dry.

A lawn to the north (facing Forest Park) would slope gradually down to a lake, which was never built. At the far eastern terminus of the spine, Tower A would stand atop a tall earthen berm. That berm and Tower A would jut out into the lake like Cahokia Mound rising above the flood plain. Across the lake would stand the theatre.

With the exception of the lake, much of the complex was built as designed. It has seen few alterations in half a century, with the exceptions of the ever growing surface parking lots to the south and the removal of some trees.

Weese’s structures float above a first floor of brick pilotis (piers) set on a concrete base. A fourth floor projects out from the mass of the building. Stair towers on the south side of the spine break up that facade, while the north facade accentuates the horizontal line of the complex. Weese designed bands of windows set back deeply from the brick facade, providing dramatic shadow lines. Perpendicular passageways pierce the spine at regular intervals, providing transparency through the brick spine. The red brickwork itself provides a texture and warmth not often seen in brutalist works from the period. Kiley intended his trees, once mature, further to soften the massing of the ensemble.

Together, Weese and Kiley created a modern center for public education that was simultaneously dense, urban and green. The master plan was approved in February 1965 and the initial building designs in June of that year. Rallo Construction and Kloster Construction built the complex. A spread in the Post-Dispatch on August 20, 1967 noted that between 4,000 and 5,000 students were inspected to enroll that fall, even though half the buildings were still under construction.

Thirty years after its construction, an article in Inland Architect extolled the design.

The student union, library, classroom and theatre buildings are models of how well buildings can be designed. Really virtuoso performances of structural/architectural spatial configurations, superb natural lighting and well-appointed materials, and the brick cladding is beautifully detailed.

Demolition for Towers A & B

Brutalism in architecture drew its name from the French brut—raw—referring to the raw or unfinished concrete surfaces favored my many mid-century architects. Even where brutalism adapted to other materials, it was typically massive in scale and sculptural in design. Brutalism was a reaction to the perceived frivolity of much modern design, a way of communicating the seriousness of architecture and of buildings and of the uses they serve. As such, brutalism found its most common expression in government and educational uses. But brutalism always had its detractors who perceived many such buildings as cold, totalitarian and … well … brutal.

After being maligned for decades, movements now are underway to preserve brutalist designs. In a culture that prioritizes the new, a 50-year-old design is often the most endangered. And Weese and Kiley’s design is now in its fifties. If the campus of St. Louis Community College—Forest Park is brutalism, then it is a very subtle, warm and humane brutalism. If you can look beyond the unfortunate parking lots and the bathrooms and fixtures that haven’t been updated in fifty years, the fact remains. Weese and Kiley’s design is stunningly good mid-century architecture.

In architecture, there are permanent buildings and then there are buildings that are disposable.

The school administration’s current plan is to build a $32 million 65,000 square foot Allied Health Building on Dan Kiley’s lawn facing Oakland Ave. The school will demolish Weese and Associates’ berm-topping Tower A—the most graceful in the complex—as well as Tower B. They will preserve the school’s surface parking lots.

In 1994, Weese and Kiley’s design for Forest Park Community College won the first ever 25-Year Award bestowed by the American Institute of Architects, St. Louis Chapter for buildings that have “withstood the test of time.” Twenty-three years after that award, the school’s leadership is seeking demolition.

Here we have the work of Harry Weese, that modernist who stood out for his advocacy to preserve our built history, and who simultaneously made history as one of the greats of modern architecture. And here we see a landscape by Dan Kiley, the father of modern landscape architecture. Here we see something permanent. And here we see plans to remove it for something disposable.

Notes:

1.https://placesjournal.org/article/the-architecture-of-harry-weese/

2.http://www.grahamfoundation.org/grantees/5086-creative-syncretism-the-early-architectural-works-of-harry-weese-columbus-indiana

Apr 11

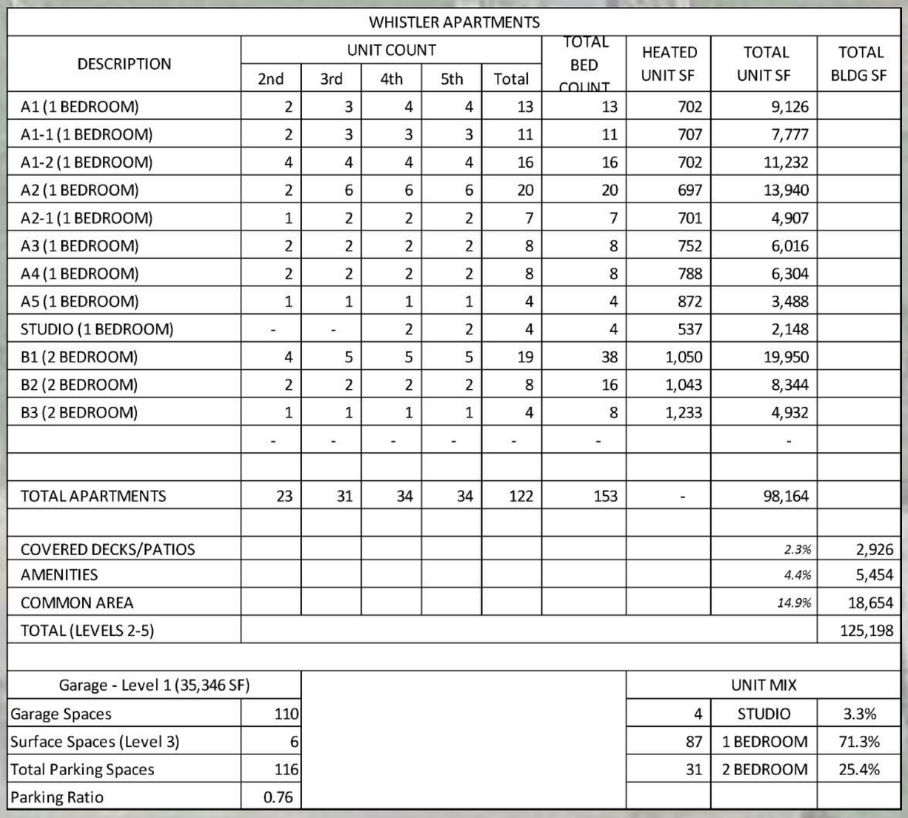

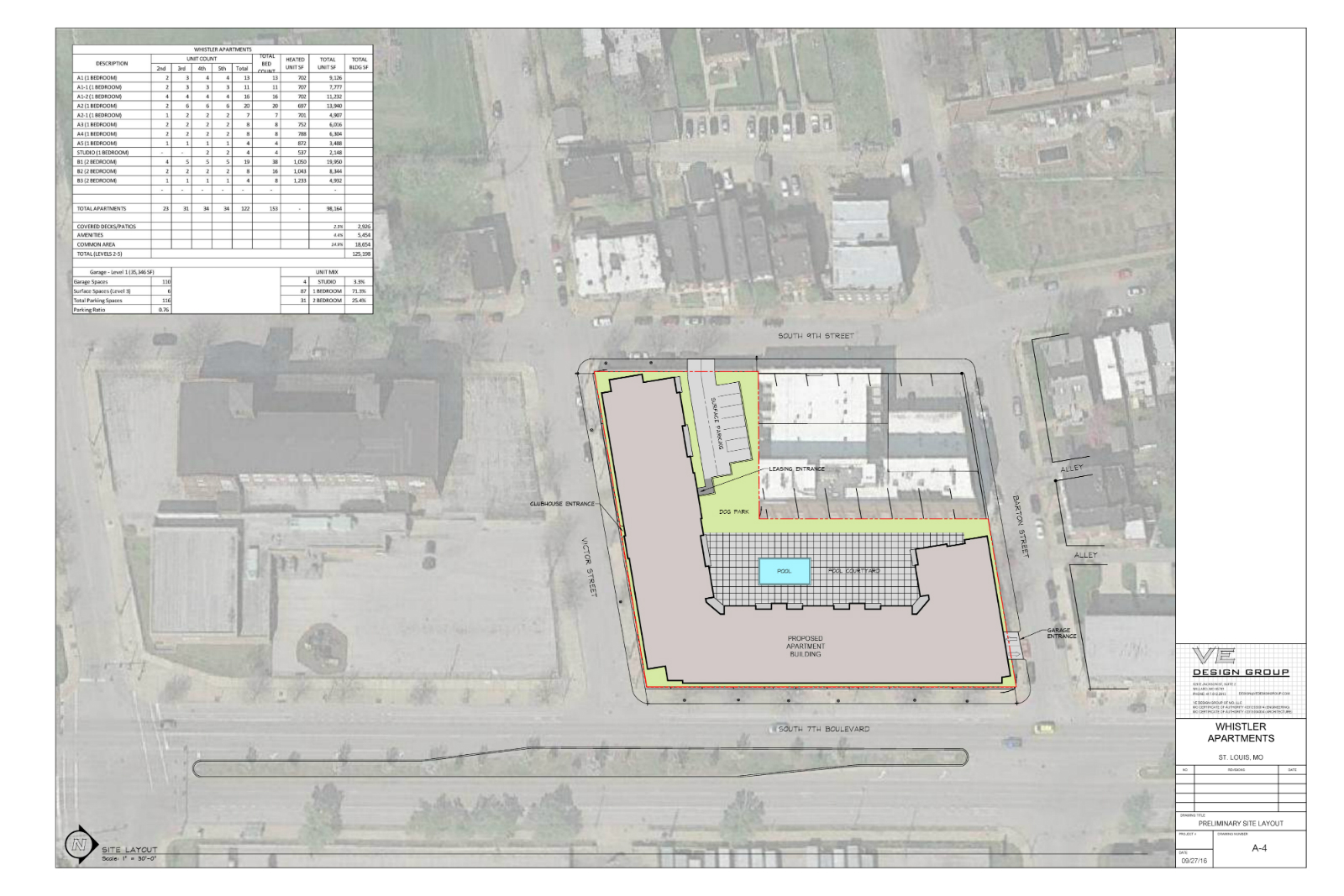

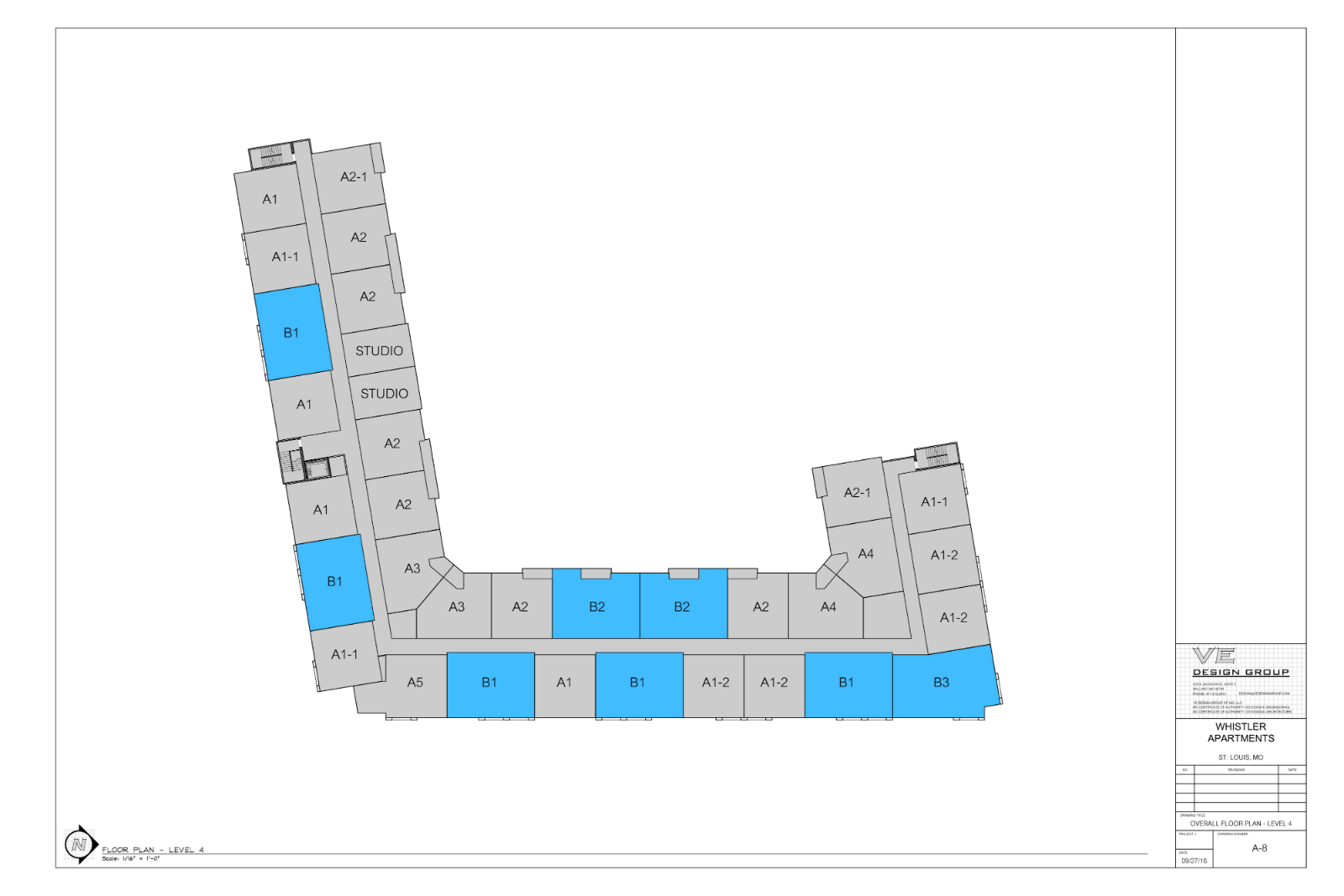

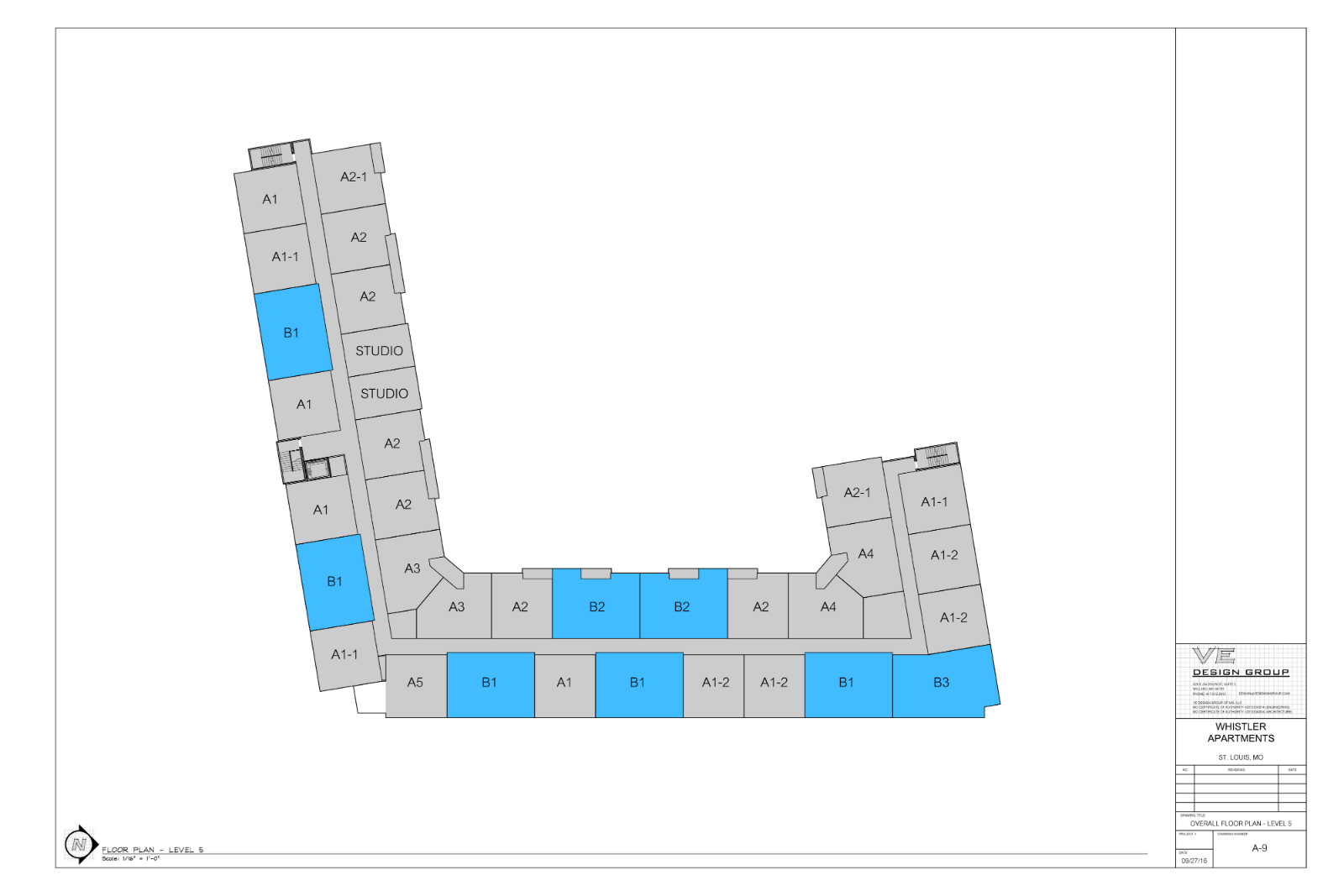

Design Evolves as Five-story, 122-Unit Soulard Project Nears Start

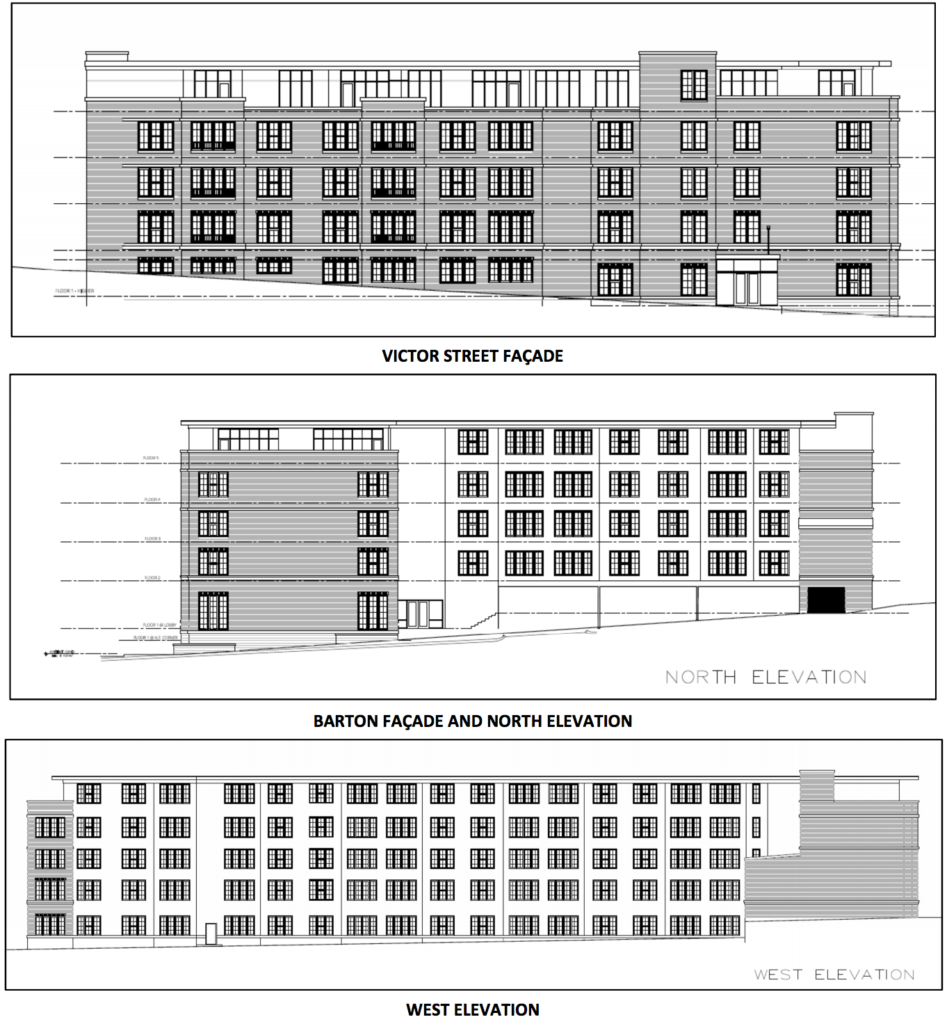

Design details for a five-story, 122-unit apartment building in Soulard continue to evolve. The project, which gained approval from the city’s Cultural Resources Office and Preservation Board nearly a year ago. The building, designed by VE Design Group, has taken on a much more block warehouse appearance. The building address is listed as 2424 S. 9th Street (map).

Along with the 126-unit project nearly underway at the other end of the neighborhood (map: 1302 Russell Boulevard), Soulard is set to see the addition of hundreds of new residents and the remake of two major underutilized sites.

__________________________________________

From our previous report: Five-story, 118 Unit Apartment Building Proposed for 7th at Victor in Soulard

Last week we mentioned an interesting residential infill project proposed for Soulard, immediately next to the recently completed Soulard IceHouse historic renovation. A rendering (though of low-resolution) of that proposal appears in the city’s Preservation Board Agenda posted online.

The city’s Cultural Resources Office recommends the Preservation Board, “approve the demolition of existing buildings and structures and grant preliminary approval to the proposed new construction”. The project would replace two brick buildings at 721 Victor Street and an adjacent structure.

From the agenda:

THE PROJECT:

Whistler One L.L.C. has provided copies of contract for the purchase of four parcels at 2403, 2405, and 2415-17 S. 7th Boulevard and 721 Victor Street that it proposes to redevelop. The project would entail the demolition of a number of small warehouses and industrial structures: two buildings on the Victor Street property, one a Merit building and the other non-contributing, being constructed after both 1929, the date used in the Soulard Neighborhood Local Historic District Standards for the end of historic significance, and 1941, the cut-off date for contributing resources in the Soulard National Register Historic District; 2415-17 S. 7th Boulevard, Victor Iron Works, consisting of small buildings along S. 7th and a storage yard with a structure supporting traveling cranes at the corner of S. 7th and Victor Street, and another yard on the north side; and a Merit building at the corner of S. 7th and Barton Street. The new building proposed to replace them would be a five-story apartment building of 118 units with 59 on-site parking spaces.

There’s more on the myriad of National Register of Historic Places nominations as well:

St. Louis City Preservation Review Board – Final Agenda 04/25/2016 by nextSTL.com

Feb 15

City Foundry Signs Zara, Patagonia, Reformation, Need Supply, and Others

Will City Foundry, the $340M project set to re-imagine a long-vacant manufacturing site in the center of St. Louis City…