We’re big fans on infill townhomes in St. Louis. The relative density of these projects, large and small, fits well in the historic scale of much of the city. Townhomes present a so-called gentle density, adding more residents to the city without introducing large apartment buildings. And the economics are smart for the city as well, as property tax revenue per acre is significantly greater with townhomes than single-family dwellings.

Two three-unit projects in Soulard and two two-unit townhomes in the Fox Park neighborhood look to continue this trend. All are located in local historic districts and so are reviewed by the city’s Cultural Resources Office and Preservation Board.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

1851 Menard Street – Soulard Historic District

OWNER/DEVELOPER: JS Community Builders LLC/Justin Hemkens

ARCHITECT: Feeler S Architects

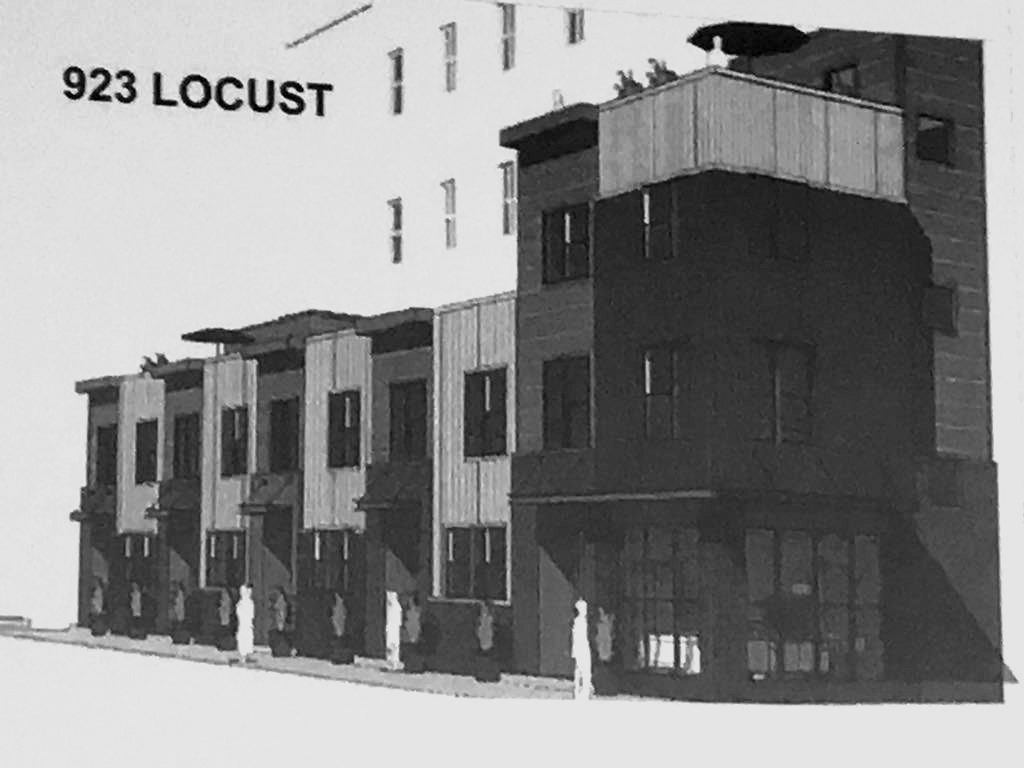

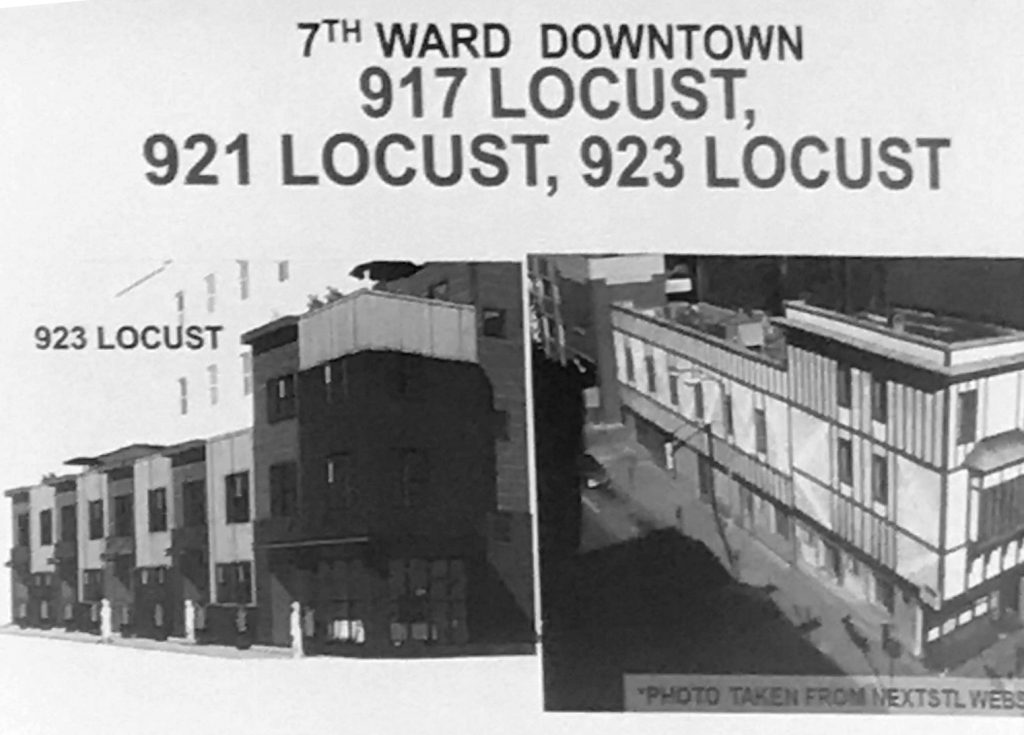

THE PROJECT: The project proposes to construct three attached townhouses with first-story garages on a vacant site on the west side of South 10th Street, adjacent to Interstate 55.

PRELIMINARY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSION: The Cultural Resources Office consideration of the criteria for new construction in the Soulard Historic District led to these preliminary findings:

- 1851 Menard Street is located in the Soulard Neighborhood Local Historic District.

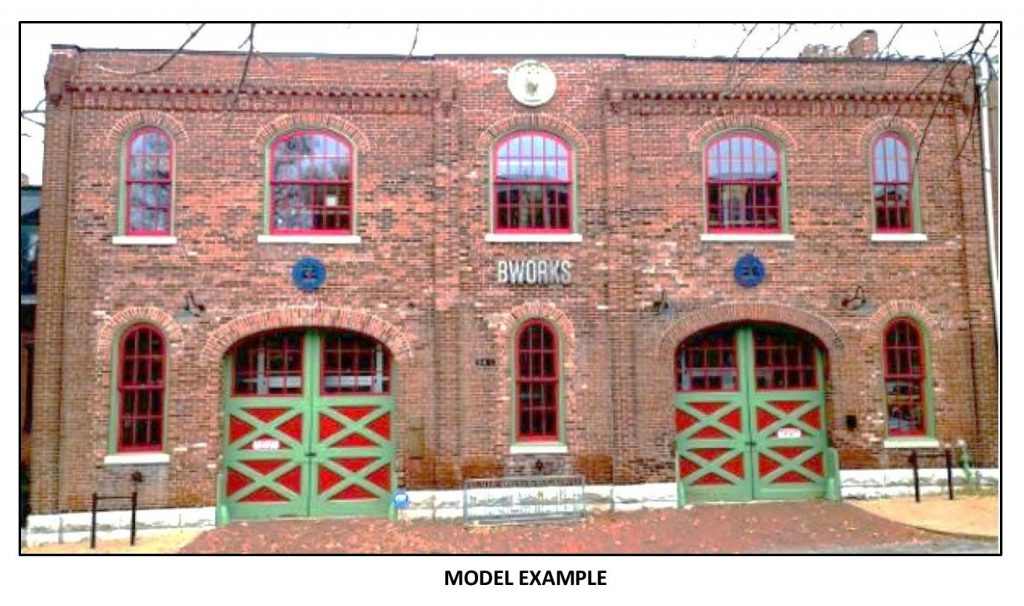

- The applicant has provided an appropriate Model Example for the proposed new construction.

- The project generally complies with the requirements of the Standards to follow a Model Example except in the areas of scale and foundation material.

Based on these preliminary findings, the Cultural Resources Office recommends that the Preservation Board grant preliminary approval for the proposed new construction with the stipulation that final plans and design details will be approved by the Cultural Resources Office for compliance with the district standards.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

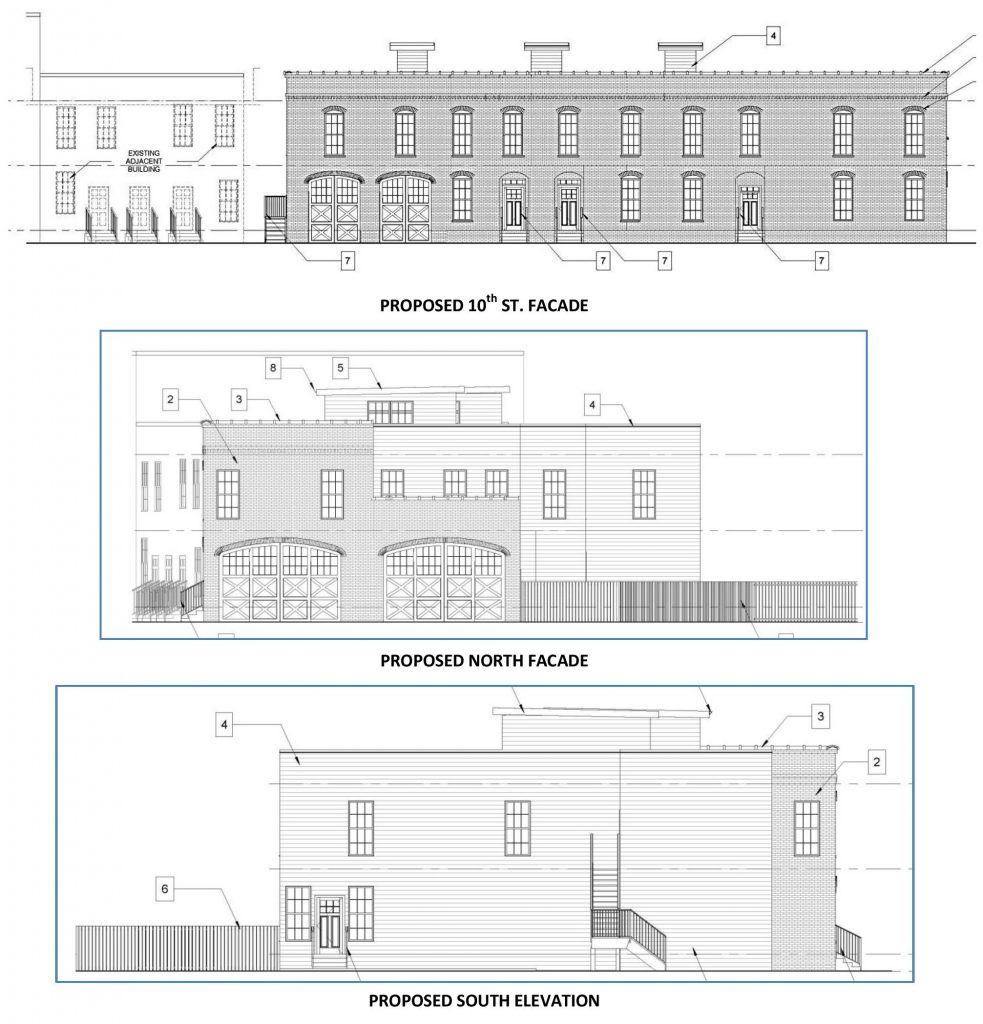

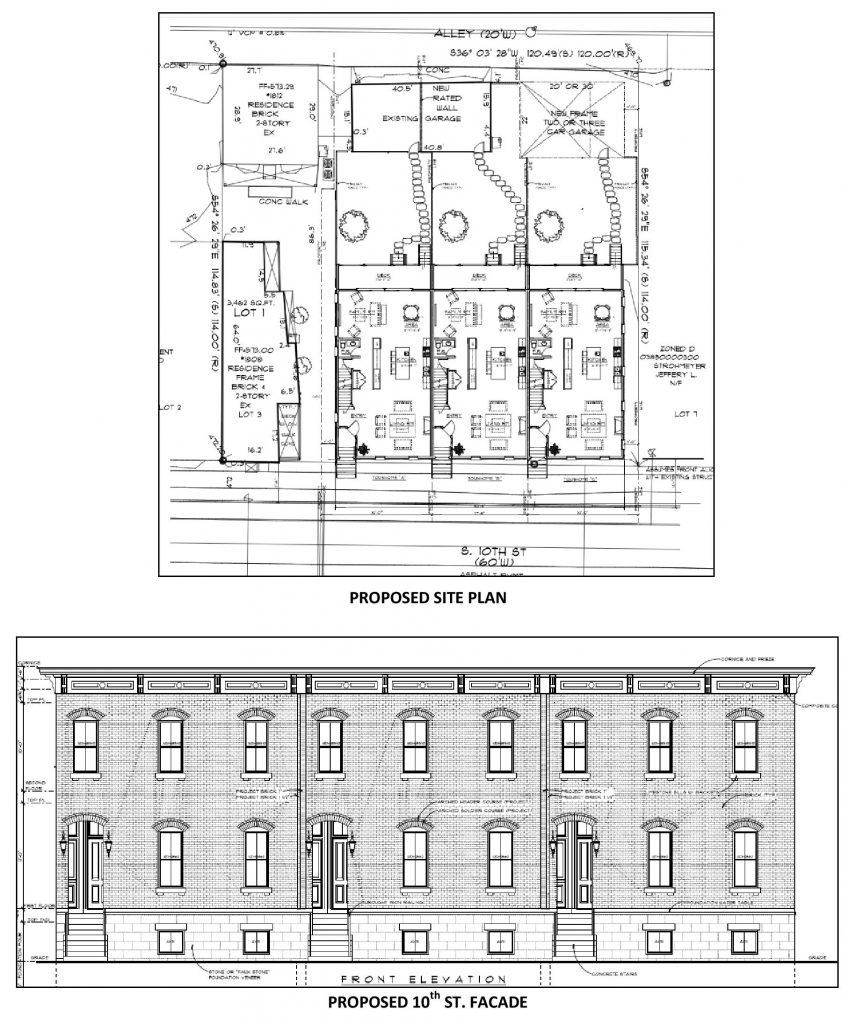

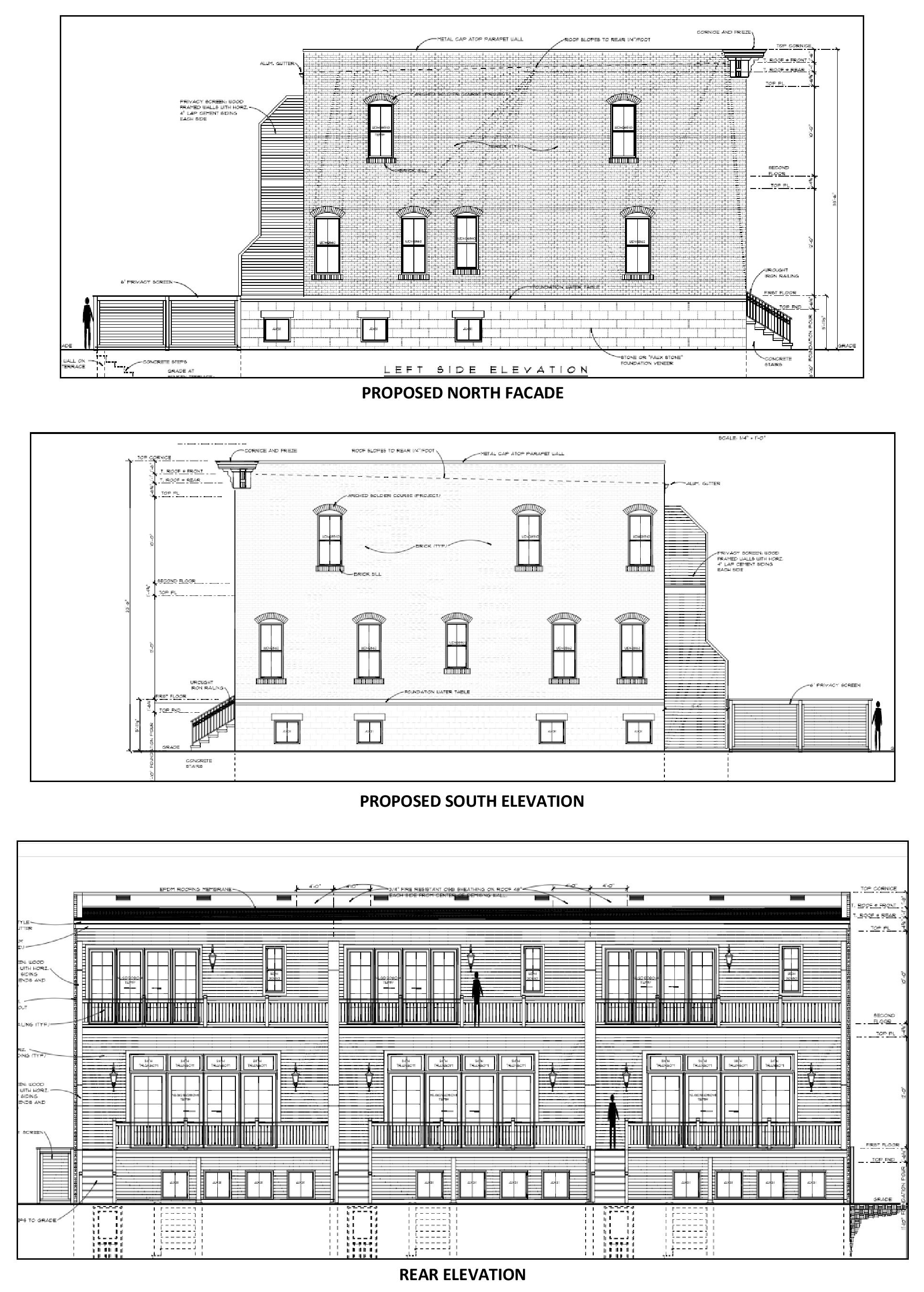

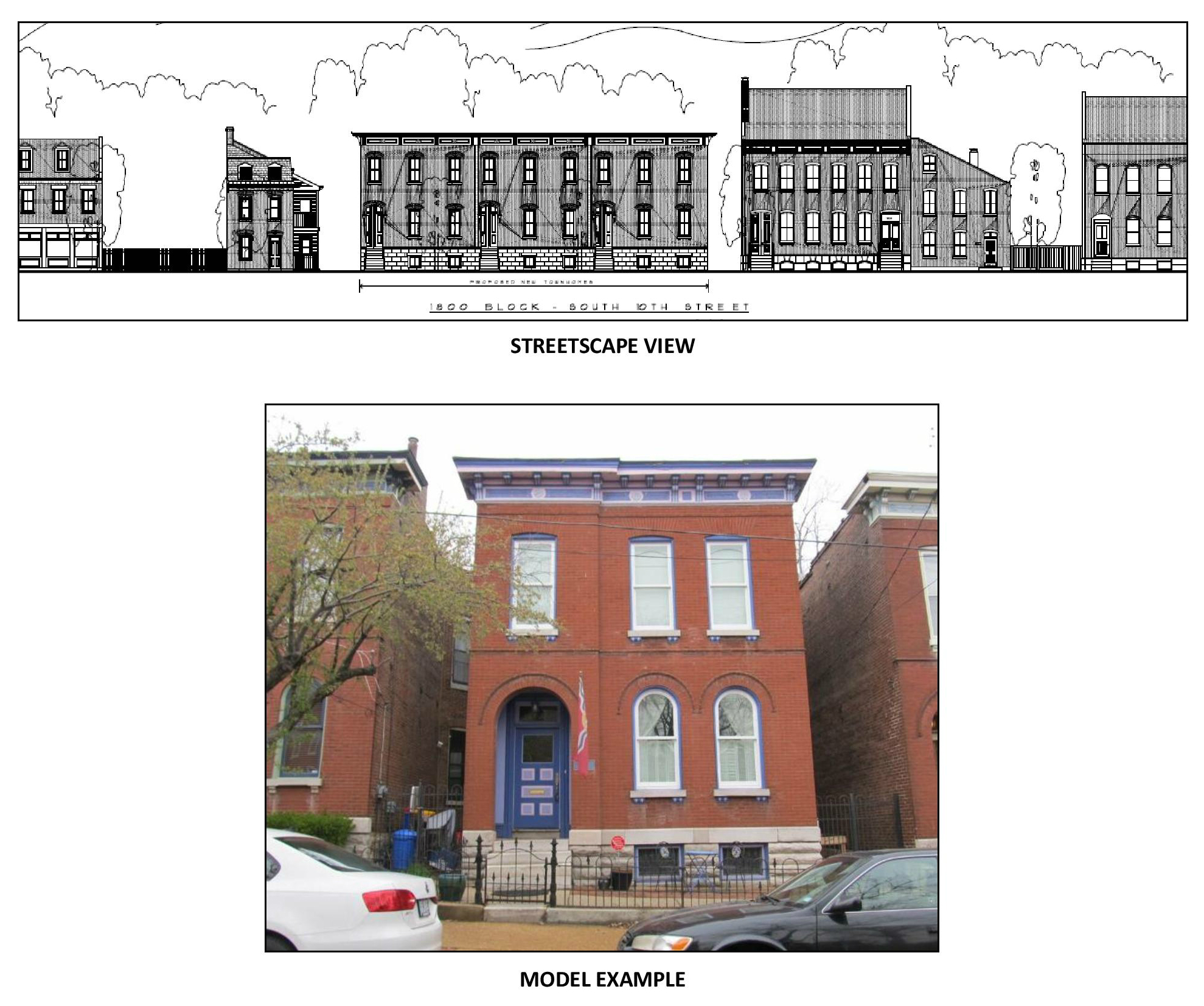

1810 South 10th Street – Soulard Historic District

OWNER/DEVELOPER: Dan Holak

ARCHITECT: Keith Schroeder

THE PROJECT: The project proposes to construct three attached townhouses on the east side of South 10th Street on a vacant site in the Soulard Local and National Register Historic District. As a new construction project, the Cultural Resources Office scheduled it for review by the Preservation Board.

PRELIMINARY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSION: The Cultural Resources Office consideration of the criteria for new construction in the Soulard Historic District led to these preliminary findings:

- 1810-20 South 10th St. is located in the Soulard Neighborhood Local Historic District.

- The applicant has provided an appropriate Model Example for the proposed new

construction. - The proposed design complies with most of the requirements of the Soulard Historic

District standards.

Based on these preliminary findings, the Cultural Resources Office recommends that the Preservation Board grant preliminary approval for the proposed new construction with the stipulation that final plans and design details will be approved by the Cultural Resources Office for compliance with the district standards.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

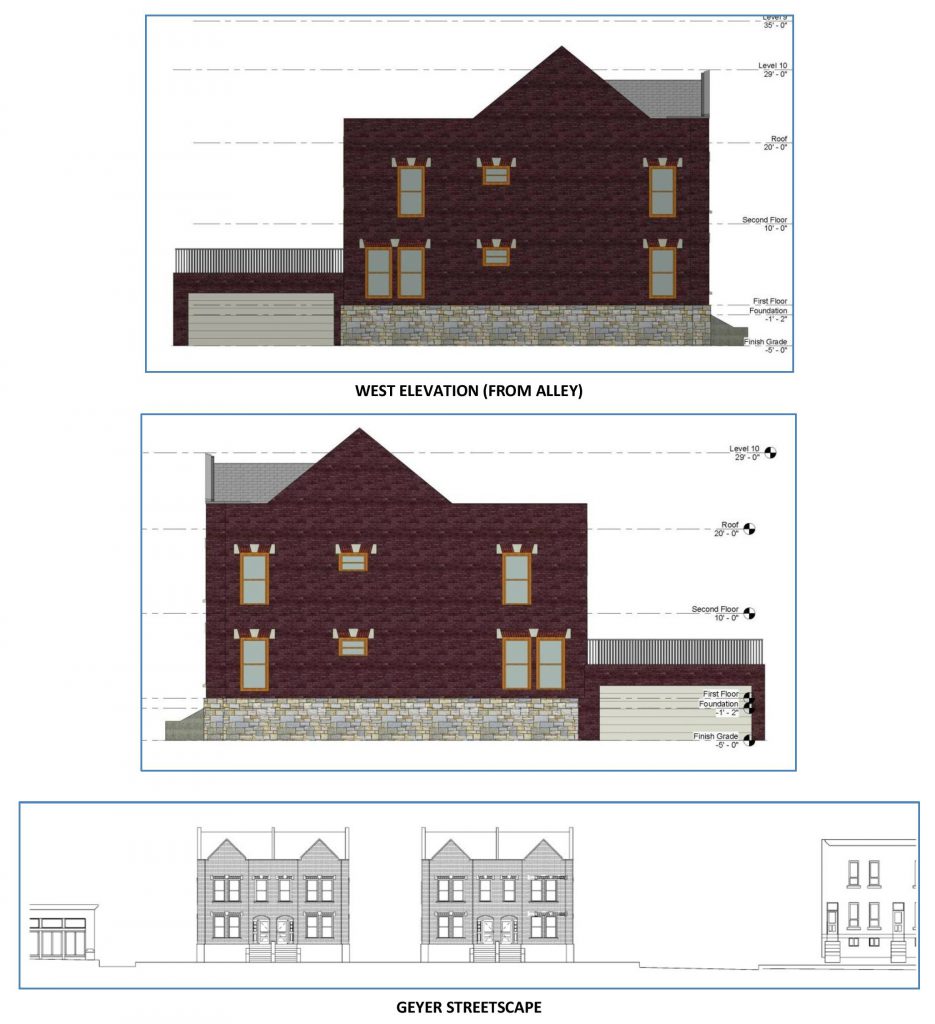

1827 California – Fox Park Historic District

OWNER/APPLICANT: Schill Investment Fund LLC/Tim O’Donnell

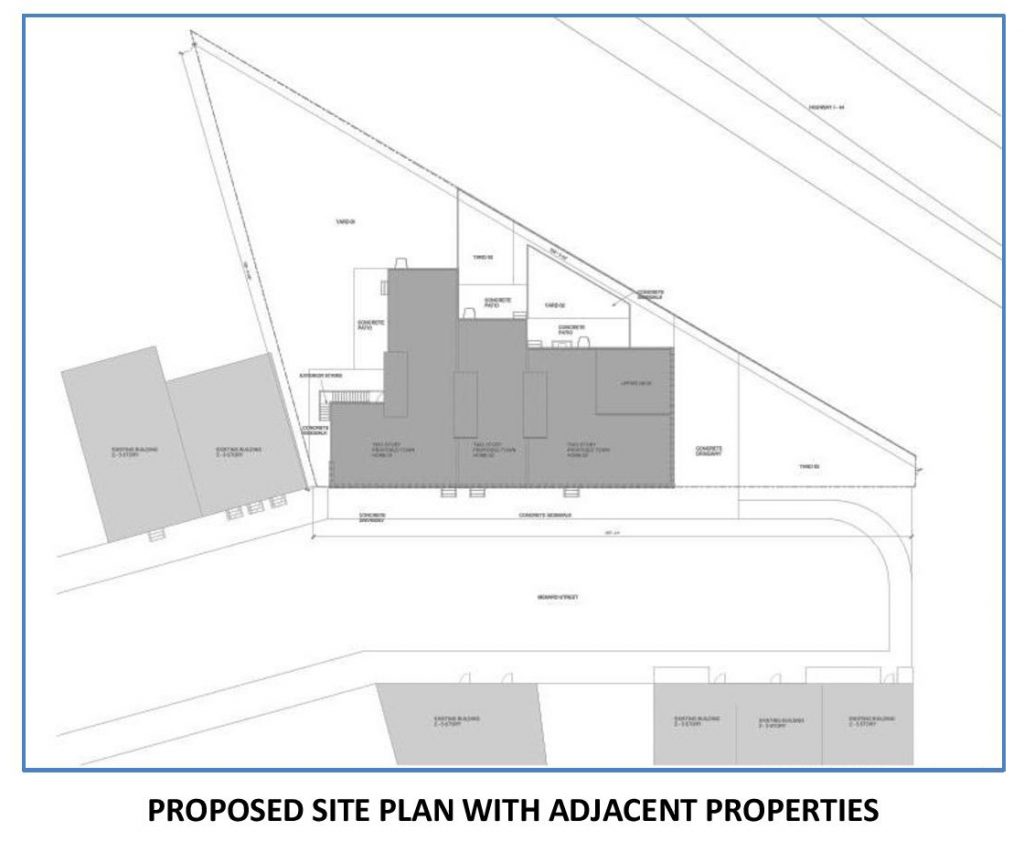

THE PROJECT: The developer proposes to construct two 2-family townhouse buildings with attached rear garages on a currently vacant site at the northwest corner of Geyer and California Avenues. The property is directly adjacent to Interstate 44 at the north boundary of the Fox Park Local Historic District.

PRELIMINARY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSION:

The Cultural Resources Office’s consideration of the criteria for new fences and retaining walls in the Fox Park Historic District Standards led to these preliminary findings:

- 1827 California Avenue is located in the Fox Park Neighborhood Local Historic District.

- While the applicant has not provided a specific Model Example for the proposed new construction, the design of the proposed buildings follows historic precedent.

- The project generally complies with the Fox Park District Standards for New Construction.

- The unusual characteristics of the site, with no rear alley, require that access be provided from California and Geyer.

Based on the Preliminary findings, the Cultural Resources Office recommends that the Preservation Board grant preliminary approval to the project, subject to the stipulation that final plans and design details will be approved by the Cultural Resources Office for compliance with the district standards.

{Small businesses along Gravois. Pedestrian-oriented commercial buildings can struggle along high-speed roads.}

{Small businesses along Gravois. Pedestrian-oriented commercial buildings can struggle along high-speed roads.} {Gravois at Jefferson, looking northeast, in its new configuration. A lane of traffic was removed in each direction, and replaced with bike lanes and a center turn lane. The road now also has several “zebra crosswalks” that increase pedestrian visibility.}

{Gravois at Jefferson, looking northeast, in its new configuration. A lane of traffic was removed in each direction, and replaced with bike lanes and a center turn lane. The road now also has several “zebra crosswalks” that increase pedestrian visibility.}

We’re in University City now. I feel much safer. We see some of the effects of #fragmentation.

We’re in University City now. I feel much safer. We see some of the effects of #fragmentation. The trolley stop at Limit. Here the platforms have the fancy texture unlike the ones in St. Louis.

The trolley stop at Limit. Here the platforms have the fancy texture unlike the ones in St. Louis. U City has put out dual trash-recycling bins. Something to copy on the city side. U City still has old-timey parking meters.

U City has put out dual trash-recycling bins. Something to copy on the city side. U City still has old-timey parking meters. The intersection of Westgate and Delmar. It has a couple of the corner curb cuts.

The intersection of Westgate and Delmar. It has a couple of the corner curb cuts. Melville at Delmar. Now this is the right way to do curb cuts!

Melville at Delmar. Now this is the right way to do curb cuts! Ackert Walkway, part fo the Centennial Greenway, and Chuck Berry Statue.

Ackert Walkway, part fo the Centennial Greenway, and Chuck Berry Statue.

The Trolley stop at Leland.

The Trolley stop at Leland. THe most awkward set of curb cuts on the Trolley corridor. The west one takes you way out of your way and the east one makes you deal with an obstacle course. Why is this so hard?

THe most awkward set of curb cuts on the Trolley corridor. The west one takes you way out of your way and the east one makes you deal with an obstacle course. Why is this so hard? American National Insurance Building. This building has an interesting history. I dislike how confining the colonnade is.

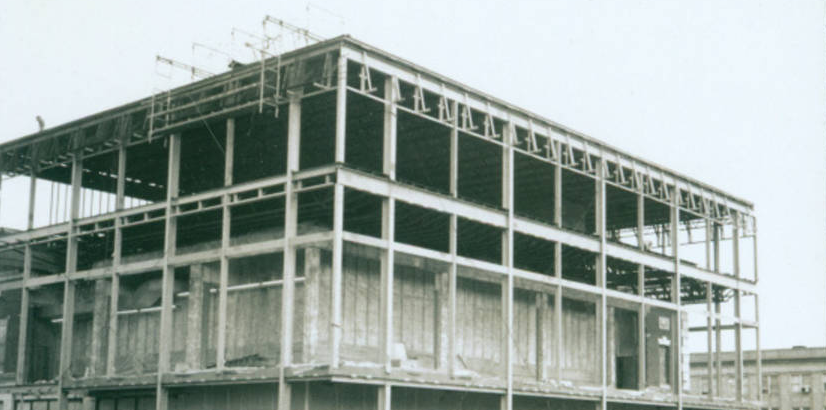

American National Insurance Building. This building has an interesting history. I dislike how confining the colonnade is. The building was stripped and a third story was added during the urban renewal era.

The building was stripped and a third story was added during the urban renewal era. I never understood why this building wasn’t set back to line up with the adjacent building. The sidewalk is too narrow.

I never understood why this building wasn’t set back to line up with the adjacent building. The sidewalk is too narrow. 6680 Delmar. The 5/3 Bank branch that never was.

6680 Delmar. The 5/3 Bank branch that never was. The Trolley stop at the University City Library.

The Trolley stop at the University City Library. The end of the line. It was once planned to do a loop around the roundabout to the west.

The end of the line. It was once planned to do a loop around the roundabout to the west.